A traditional Japanese Deba knife with a single-bevel blade and wooden handle, used for filleting fish.

GENSAKU

GENSAKUDeba knives (pronounced “deh-bah”) are traditional Japanese kitchen knives known for their thick, heavy blades and exceptional ability to butcher and fillet fish.

In Japanese, the Deba knife is called “Deba bōchō” (出刃包丁), which literally means “pointed carving knife”.

This hefty single-bevel knife originated in Sakai, Japan during the Edo period and was purpose-built for tasks like beheading fish and cutting through fish bones. Unlike lighter all-purpose knives, a Deba’s extra weight and thickness provide the stability and cutting power needed to break down whole fish with ease.

Despite its specialization, the Deba isn’t only for fish. Many Japanese chefs also use Deba knives for tasks like cutting poultry or sections of meat on the bone. In fact, there is no dedicated “meat cleaver” in traditional Japanese cuisine – so the stout Deba often doubles as a butcher’s knife for smaller bones.

Listen up, kid: a Deba ain’t for hacking through big livestock bones—clobber a hefty beef or pork joint and you’ll chip the edge in no time. Where a Deba truly shines is breaking down fish and small game, keeping the flesh pristine thanks to that razor-sharp edge.

One interesting bit of lore surrounds the origin of the name “Deba.” According to one popular theory, the first blacksmith in Sakai to create this knife had pronounced buckteeth – in Japanese, “deppa” means protruding teeth – and the distinctive knife was humorously named after his appearance.

True or not, that little legend does give the Deba a special charm in our kitchen lore. What we can say with confidence is that this knife has served us for centuries, treasured for its strength and precision whenever we’re preparing fish.

By using the right knife for the right job (for example, using a Deba for fish instead of a flimsy general knife), you minimize damage to the ingredients’ cells and preserve flavor, especially for delicate sashimi. In short, the Deba is indispensable for Japanese chefs who prepare whole fish, and it’s a knife style that has stood the test of time in Japan’s seafood-centric cuisine.

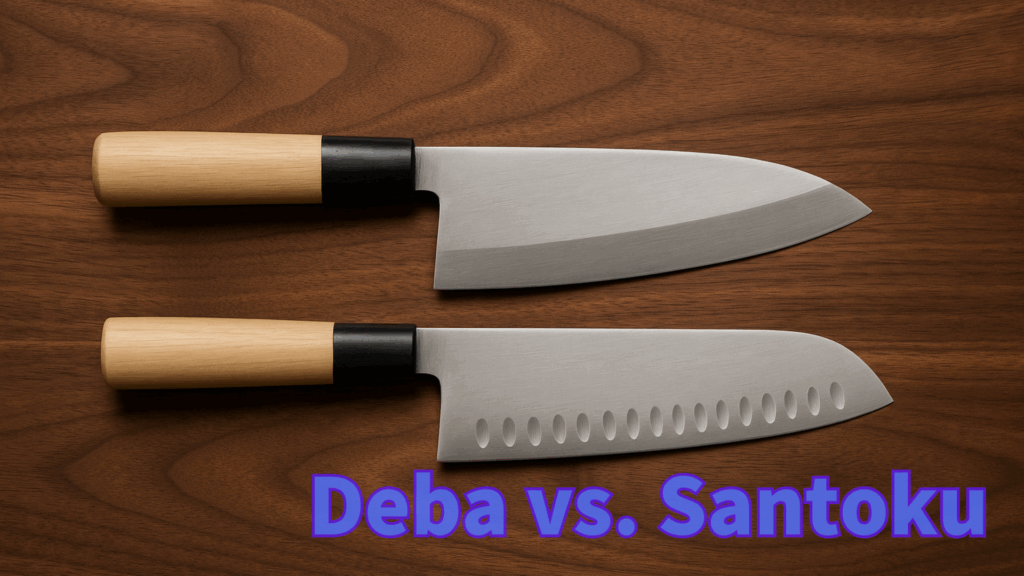

Deba vs. Santoku: What’s the Difference?

At first glance, a Deba knife’s broad leaf-shaped blade might look a bit like a Santoku knife (another common Japanese kitchen knife). Both knives often have a similar length (between 5–8 inches) and shape. So, Deba vs Santoku – how do they differ? The main differences come down to the blade grind, thickness, and intended use.

If you don’t mind my saying, the santoku is our gentle, all-purpose companion. Its name—“three virtues”—speaks of meat, fish, and vegetables, and the blade’s double bevel, slender profile, and light weight make it ideal for everyday slicing and chopping across that whole range.

The deba, by contrast, is a specialist. With a single-beveled edge and a far thicker, heavier spine, it is crafted for the decisive work of butchering fish and gliding cleanly through bones.

Below is a comparison of the key differences between a Deba knife and a Santoku knife:

| Comparison Item | Deba Knife (出刃包丁) | Santoku Knife (三徳包丁) |

|---|---|---|

| Bevel (Edge Grind) | Single-bevel (flat on one side, angled on the other) | Double-beveled (symmetrically sharpened on both sides) |

| Blade Thickness & Weight | Thick and heavy. Built with a stout spine and heft to cut through fish heads and small bones with stability. May feel weighty in hand. | Thin and light. Much slimmer blade profile for agility. Easy to maneuver for fine cuts and quick chopping of a wide range of ingredients. |

| Blade Shape & Tip | Wide, pointed tip. Broad blade width with a slightly angled, acute tip. The spine is very thick and sturdy. This shape allows detailed work around fish bones (like trimming ribs or scraping). | Rounded tip, wider belly. The tip is more rounded and the edge has a longer flat contact with the cutting board. The overall shape is optimized for rocking and chopping – truly multi-purpose. |

| Primary Uses | Fish butchery: Designed to chop off fish heads, slice through fish bones, and fillet whole fish (three-piece filleting). Also suitable for trimming meat off bone (e.g. poultry). Essentially a fish and protein breakdown knife. | All-purpose: Meant for cutting meat, fish, vegetables in general prep. A household “utility” knife used for most daily cooking tasks. Not intended for heavy bone cutting. |

As shown above, a Santoku knife is a versatile home kitchen workhorse – great for everyday slicing and dicing with its lighter build – whereas a Deba knife is a heavy-duty tool tailored for specific butchery tasks (especially fish). In practice, this means a Santoku is easier for prolonged use and fine slicing, but it would struggle or even be damaged if you tried to hack through fish heads or dense bones.

Alright, let me put it to you straight. The Deba’s got a thick spine and a single-sided edge, so it’ll lop off fish heads and break down a whole fish without bending or chipping. Now, that same one-bevel grind means it’ll wander on you when you try to make straight cuts through vegetables—it pulls to the chisel side—so it’s no good for everyday veggie work. Bottom line? A Santoku is your lightweight, do-it-all knife for daily cooking, while the Deba is a heavy, single-bevel beast built for butchering fish and bone-in proteins. They both belong in the kitchen, but they’re meant for very different jobs.

How to Use a Deba Knife (Step-by-Step for Filleting Fish)

One of the hallmark uses of a Deba knife is filleting whole fish. The Deba’s design makes tasks like removing scales, cutting off the head, and filleting the fish into neat portions much easier and cleaner than using a regular chef’s knife.

Here we’ll walk through the typical steps of using a Deba to process a fish (also known as performing a san-mai oroshi – cutting the fish into three “fillets”: two filets plus the backbone piece). This process will illustrate the proper Deba knife use and techniques:

Before cutting, you’ll want to remove the fish scales. Hold the Deba knife upside down (sharp edge facing up) so that you can use the spine (back) of the blade. Starting from the tail and moving toward the head, scrape the spine’s corner against the scales. Use short strokes and a slight angle to effectively lift the scales. Tips: Keep the edge (beveled side) of the knife facing upward as you scrape with the spine – this lets the rigid spine corner pop the scales off without cutting into the skin. Be thorough around the fin areas (especially near the dorsal and tail fins) since scales tend to hide there. The Deba’s thick spine won’t bend, so you can apply moderate pressure to remove even stubborn scales. Always wash and pat the fish dry before scaling (for hygiene and a better grip).

Next, it’s time to cut off the fish’s head. Lay the fish on a cutting board and position the Deba’s blade just behind the gills (where the head meets the body). Press down firmly and slice through in one motion, using the weight of the knife to help cut through the backbone. The Deba’s hefty blade and sharp edge should sever the head cleanly. Tips: Make sure the edge of the knife is in full contact with the board before pressing through – this ensures you cut all the way and don’t leave any connected bits. It can help to use a slight rocking or pulling motion as you cut: start the cut with a downward push, then draw the knife towards you to finish slicing through the bone. This “draw cut” technique uses the Deba’s sharp edge effectively and is safer than trying to force straight down. Never try to “chop” by hammering the Deba – let the knife do the work with steady pressure and a slicing motion. With practice, you’ll lop fish heads off in one smooth cut. The Deba can also be used to cut through other tough parts, like the fish’s tail or any large bones that need removal at this stage.

After the head is off, you’ll remove the internal organs (gutting the fish). Insert the tip of the Deba into the fish’s belly (start at the anal vent on the underside) and gently slide the blade upward along the centerline to open the belly. The sharp tip will open the abdomen easily. Be careful not to insert the knife too deep to avoid puncturing organs like the bitter gallbladder. Once you’ve slit the belly open, use your hand or the knife to pull out the innards in one go. You may cut the connective tissue near the head-end to free all the guts. Dispose of the guts and rinse the fish cavity if needed. Tips: A Deba’s pointed tip excels at this belly cut, but use minimal force – it’s sharp enough that you only need a light push to avoid messily bursting any organs. Many chefs actually use the Deba’s tip and front section for delicate tasks like this, and the rear heavy section for bones and heads.

Now comes the filleting part. With the fish scaled, headed, and gutted, you can split it into two clean fillets. Lay the fish on one side. Starting at the tail end, insert the Deba’s edge along the backbone. Angle the blade slightly down toward the bones and slide it toward the head, following along the ribcage. Use the front half of the blade and a slicing motion, letting the backbone guide your knife. This will separate the top fillet from the bones. Next, flip the fish over and repeat: beginning at the tail, cut along the backbone toward the head on the other side to free the second fillet. Finally, if any rib bones remain attached to the fillets, use the Deba to carefully trim them off (almost like shaving them away). In the end, you should have two boneless fillets and the central bone frame. Tips: The key is to keep the knife against the bones as you slice, to avoid wasting meat. The single-bevel edge of the Deba is great for hugging the flat surface of bones. Use smooth, long strokes rather than chopping motions. Many Japanese chefs will do this in one motion per side, but take multiple gentle passes if you’re a beginner. The Deba’s sharpness is crucial here – a well-honed Deba will “slide” along the bones with minimal effort, almost as if it’s guided by them. Once done, you’ve completed a three-piece fillet using just one knife. Congrats – the Deba knife can single-handedly accomplish the entire fish filleting process!

When you go through each step, you’ll understand why we hold the Deba so close to our hearts for fish work. With this one knife you can scale, gut, make a clean chop through the bones, and finish with precise filleting. It’s wonderfully versatile—guiding you from a whole fish to tidy, beautiful fillets, all ready for sushi, sashimi, or any cooking you have in mind.

Deba Knife Care and Maintenance

Now, here’s the thing: most Deba knives are forged out of high-carbon steel—that’s how we get ’em so razor-sharp. But that also means you’ve got to baby ’em a bit. Whether your Deba’s carbon steel or stainless, guard that edge like gold and keep rust at bay. A little care goes a long way to keep that blade in fighting shape.

Here are key Deba knife maintenance tips to ensure your knife lasts a lifetime:

Wash and Dry Immediately After Use:

After cutting fish (which contains salt and protein), rinse the blade promptly. Fish blood and juices are corrosive and can lead to rust if left on the blade. Use a gentle dish soap and a soft sponge to clean the knife – avoid abrasive scrubbers or steel wool, as those can scratch or dull the blade edge. Once washed, dry the knife thoroughly with a clean towel. Pay special attention to the area where the blade meets the handle and the back of the blade, as water can hide there. Any moisture left can induce rust, especially on carbon steel.

Oil the Blade (for Carbon Steel Deba):

If your Deba is made from carbon steel (which is prone to rust), it’s wise to apply a thin coat of oil before storage. Food-safe oils like mineral oil, camellia oil (traditional tsubaki oil), or even a bit of cooking olive oil can be used. This light oil layer forms a protective barrier against humidity. You don’t need to soak it – just a light wipe will do. Remember to wipe the blade clean of oil before the next use (especially if using a food oil that could go rancid).

Regular Sharpening:

A sharp Deba is safer and more effective than a dull one. When a Deba’s edge starts to dull, you may apply excess force, which can damage the blade or slip and hurt you. Hone or sharpen the knife periodically to keep the edge keen. Most Deba knives are single-beveled, so sharpening involves working the bevel side at the appropriate angle and just lightly deburring the flat side. Typically, you might sharpen the bevel side at around a 15°–20° angle, and on the flat side just remove the burr. If you’re new to sharpening single-bevel knives, it’s worth practicing or consulting a guide to maintain the correct edge geometry.

Proper sharpening will not only restore performance but also extend the knife’s life. (Note: “Burr” or koba is the tiny roll of steel that forms on the opposite side of the edge when sharpening – you’ll feel it as a slight catch; it should be gently honed off for a clean edge.)

Safe Storage:

Store your Deba in a dry, well-ventilated place. Avoid leaving it in damp areas like under-sink cabinets. It’s best to keep the knife separated from other metal tools to prevent the edge from knocking against hard objects (which could cause chips in the blade). Using a blade guard (saya sheath or a plastic edge guard) is highly recommended – it protects the blade from damage and also protects you when reaching into your knife drawer. Many Deba knives come with wooden sayas for this purpose. Always ensure the knife is clean and dry before sheathing it for storage.

By following these care steps, a quality Deba knife can truly last for decades (or even be passed down to the next generation). Traditional carbon steel Debas, in particular, reward you with exceptional sharpness if you give them the extra care they need to stay rust-free. And even stainless-clad or stainless steel Deba knives will benefit from proper cleaning and sharpening, so they perform at their best every time you use them.

Types of Deba Knives: Hon-Deba, Ko-Deba, and Mioroshi Deba

Now hear me out, kid: like most of our old-school blades, the Deba comes in a handful of sizes and styles to match the job. The everyday version—what we veterans call the Hon-Deba, the “true Deba”—runs about 165 to 210 millimeters, six to eight inches, and it’s the one you grab for your typical medium-sized fish. But you’ll also come across names like Ko-Deba and Mioroshi Deba, so keep those in mind.

Here’s what they mean:

Ko-Deba (小出刃) – “Small Deba”:

As the name suggests, a Ko-Deba is a smaller version of the Deba. Blades typically range from about 100 mm to 150 mm (4–6 inches). These mini Debas are great for small fish (e.g. anchovies, sardines, mackerel) or for delicate tasks like filleting small fish and seafood that would be overkill for a full-sized Deba. They are lighter and easier to handle for precision work on smaller ingredients. Many professionals keep a Ko-Deba on hand for when the catch of the day is petite fish. Home cooks who occasionally prep fish might find a Ko-Deba more comfortable as well, since it’s more nimble but still has the Deba’s thick spine and sharp edge. Essentially, if a regular Deba feels too large or heavy for some jobs, a Ko-Deba steps in nicely.

Mioroshi Deba (身卸出刃) – “Fillet Deba”:

The Mioroshi Deba is a variant that combines features of a Deba and a Yanagiba (sashimi knife). It is generally thinner and narrower than a standard Deba, and often a bit longer in blade length. The idea is to have a knife that can both fillet a fish (like a Deba) and also make clean slices (like a Yanagiba for sashimi) – essentially a hybrid design. A Mioroshi Deba typically still has a single bevel and is used for filleting, but because the blade is slimmer, it glides through flesh with less resistance. This makes it popular for fishmongers or chefs who do a lot of fillet work and want a lighter knife for speed.

However, the trade-off is that the Mioroshi is not as robust on very thick bones – its reduced spine thickness means you should be a bit more gentle to avoid chipping on hard fish bones. In practice, many consider the Mioroshi Deba as a cross-over knife: capable of breaking down a fish and then skinning or slicing it thinly. It’s great for those who want one knife to do almost everything in fish prep. Mioroshi Deba are often found in longer lengths (210 mm, 240 mm, even up to 300 mm) to accommodate larger fish, yet still slimmer than an equivalent hon-deba. They are lighter in weight relative to their length, which can reduce fatigue in repetitive tasks. Just remember to treat a Mioroshi more like a slicer when it comes to bones – use it for fillet cuts and medium bones, but for really tough heads or thick bones, a stout hon-deba is safer.

Western Deba (Yo-Deba):

In recent times, some manufacturers (especially those catering to Western markets) produce Western-style Deba knives. These are usually double-beveled (sharpened on both sides, like European knives) rather than the traditional single-bevel. The idea is to offer the heavy blade and shape of a Deba but in a format familiar to chefs who may not be comfortable with single-bevel sharpening or use. A Western Deba can be used similarly for fish or poultry, and the double bevel means left-handed and right-handed use is the same. Brands like Shun (Kai USA) have offered Deba knives in their western-handled series, often with a 50/50 edge. Keep in mind, a double-bevel Deba may not have exactly the same cutting feel as a classic Deba (since the geometry differs), but it can be a practical compromise for some users.

Here’s how I break it down for folks looking to buy a Deba. You’ve got three main breeds:

Hon-Deba – the classic workhorse. Medium-to-large fish? This is the one that’ll treat you right.

Ko-Deba – a little fella for small fish or cooks with smaller hands. Same muscle, just scaled down.

Mioroshi Deba – slimmer, longer, meant for gliding through fillets with real finesse.

Each style earns its keep. For most home kitchens where you tackle a whole fish now and then, a mid-size Hon-Deba—say, 165 to 180 mm—is money well spent. Start there. If you end up breaking down fish of all shapes and sizes every week, you’ll likely add another Deba or two to the rack so you’re covered no matter what swims in.

Choosing a Deba Knife (Steel, Size, and Price Considerations)

When looking to purchase the best Deba knife for your needs, consider a few key factors: the blade material, the size, and of course, your budget. Deba knives can range from affordable, machine-made blades to exquisite hand-forged works of art. Here are some pointers to help you choose:

Blade Material – Carbon Steel vs Stainless:

Traditional Deba knives are often made from high-carbon steels like White #2 (Shirogami) or Blue #2 (Aogami) steel. These carbon steels can take an extremely sharp edge and are a favorite of professional chefs. The downside is they rust easily if not cared for (as discussed in maintenance). Stainless steel Deba knives, on the other hand, offer much easier maintenance (no immediate rust worries), though they might have a slightly less razor-sharp edge compared to carbon. There are also laminated blades (e.g. carbon core with stainless cladding) that try to give the best of both – sharp core, rust-resistant exterior. If you’re new to Deba or prefer low maintenance, a stainless or clad Deba might be safer. If you want maximum sharpness and don’t mind oiling your knife, a carbon steel Deba is fantastic. Many top Japanese makers offer the same knife in either carbon or stainless versions.

Blade Length:

Deba knives come in various lengths. Common sizes for standard Deba are 150 mm, 165 mm, 180 mm, 210 mm, etc. The right size depends on the fish or ingredients you plan to cut and your comfort. For home use and average-size fish (say up to trout or salmon), a 165–180 mm (6–7 inch) Deba is very versatile. It’s large enough to handle substantial fish but still manageable. If you only deal with small fish (mackerel, etc.) or want more agility, a 150 mm or a Ko-Deba might suffice. For very large fish (tuna, yellowtail) or for professional use, 210 mm or larger gives more leverage. Keep in mind the larger the Deba, the heavier it gets – make sure you can handle the weight. As one reference point, many Japanese professionals favor around a 180 mm Deba as a “standard” – it’s kind of the sweet spot for all-purpose fish work. If unsure, err on the medium size to start.

Handle Style:

Most Deba knives feature a wa-style handle (traditional Japanese handle), often made of wood (e.g. ho wood magnolia) with a buffalo horn bolster. This keeps the knife lighter in the handle and is generally preferred for the balance on single-bevel knives. Some Deba (especially western versions) may have Western-style handles with full tangs. Handle choice is partly aesthetic and about comfort. Wa handles are usually rounded or octagonal and allow a good grip even when wet. Ensure the handle feels secure and suits your grip size. If you’re left-handed, you will need either a left-handed Deba (bevel on opposite side) or a symmetric bevel version – so handle that accordingly when choosing.

Deba Knife Price:

The price of a Deba knife can vary widely. You can find entry-level Deba knives starting around $50-$100 (often smaller sizes or machine-made stainless knives). Mid-range artisan Deba knives might range around $150-$300 depending on size, steel, and brand. High-end handcrafted Deba knives (especially larger ones or those made with premier techniques like honyaki single-piece forging) can be quite expensive – even $600+ for an 8-inch Deba from a top smith.

For example, some Sakai-made Aogami #2 Deba in 180 mm length can run around $600 due to the craftsmanship and finish. The good news is that even an affordable Deba will generally last and perform well if it’s properly maintained. When considering price, think about how often you’ll use it and the level of quality you appreciate in knives. If you are a professional or serious hobbyist breaking down fish frequently, investing in a higher-end Deba (with superb steel and balance) may be worthwhile. If you only occasionally fillet fish, a budget-friendly model can do the job. Just be sure to buy from a reputable source or brand so that you get a properly made knife.

If you’re wondering where to look, a number of trusted makers craft fine Deba knives—Sakai Takayuki, Yoshihiro, Masamoto, Shun, Global, and Misono, to name a few. Shun, for example—Kai’s well-known brand—offers a Deba fashioned from their VG-Max stainless steel, which is lovely if you’d like the traditional Japanese profile paired with the easy care of modern stainless.

Many Japanese knife aficionados will recommend looking at Sakai or Seki city knives, as those regions specialize in traditional blades. Ultimately, choose a Deba that fits your budget but also one you’ll be proud to use – a good knife can last a lifetime.

Conclusion: Should You Get a Deba Knife?

In conclusion, a Deba knife is an essential tool for anyone who frequently works with whole fish or wants to practice authentic Japanese fish butchery. Its heavy, single-bevel blade is purpose-built to glide through fish flesh and cut through bones cleanly, which not only makes the process easier but also helps maintain the quality of the meat (less crushing and tearing). While in the Japanese kitchen the Deba is mainly a fish specialist, it also has the versatility to handle poultry butchery and other bone-in meats on a smaller scale. On the other hand, if your cooking rarely involves breaking down whole fish or bone-in cuts, a Deba might not see daily use like a chef’s knife or santoku would.

Let me tell you something, pick up a Deba and you Yanks’ll open a whole new door—buy a fresh fish whole at the market, then fillet it yourself for sushi, sashimi, or the grill. Do it right and you’ll find it’s not only fun but cheaper by the pound, since you can use every last bit. Sure, the Deba has a learning curve—she’s hefty and that single-bevel edge takes getting used to—but once you tame it, the payoff is huge. Just remember, the Deba doesn’t replace your other blades; it works alongside ’em. You’ll still reach for a yanagiba for those paper-thin sashimi slices, and a petty or santoku when you’re cutting veg, and so on. Every knife’s got its job.

If you decide to get a Deba, take good care of it, and it will serve you for many years of fish feasts. Many chefs become quite attached to their Deba, viewing it as the trusty blade that enables them to break down the finest ingredients from the sea. It embodies a piece of Japanese culinary tradition – connecting you to techniques passed down through generations.

Interested in purchasing a Deba knife? Be sure to choose one that suits your needs (consider the size and steel as discussed). To help you pick the right one, we’ve compiled a list of top recommendations. Check out our separate article on the Best Deba Knives (Top 5 Deba Knife Picks), where we rank and review some of the finest Deba knives available – from professional-grade blades to budget-friendly options. It’s a great resource to see which Deba might be “the one” for your kitchen. Happy filleting!

Comments