There are two broad categories of kitchen knives used today: traditional Japanese knives (和包丁, wa-bōchō) and Western knives (洋包丁, yō-bōchō).

In this comprehensive kitchen knife comparison, we will explain the differences between these knife types in terms of blade design, usage, materials, handle design, and maintenance.

Whether you are a cooking enthusiast, a professional chef, or simply curious about Japanese culinary tools and culture, this guide will help you understand what sets Japanese and Western kitchen knives apart.

Blade Shape and Edge (Bevel) Differences

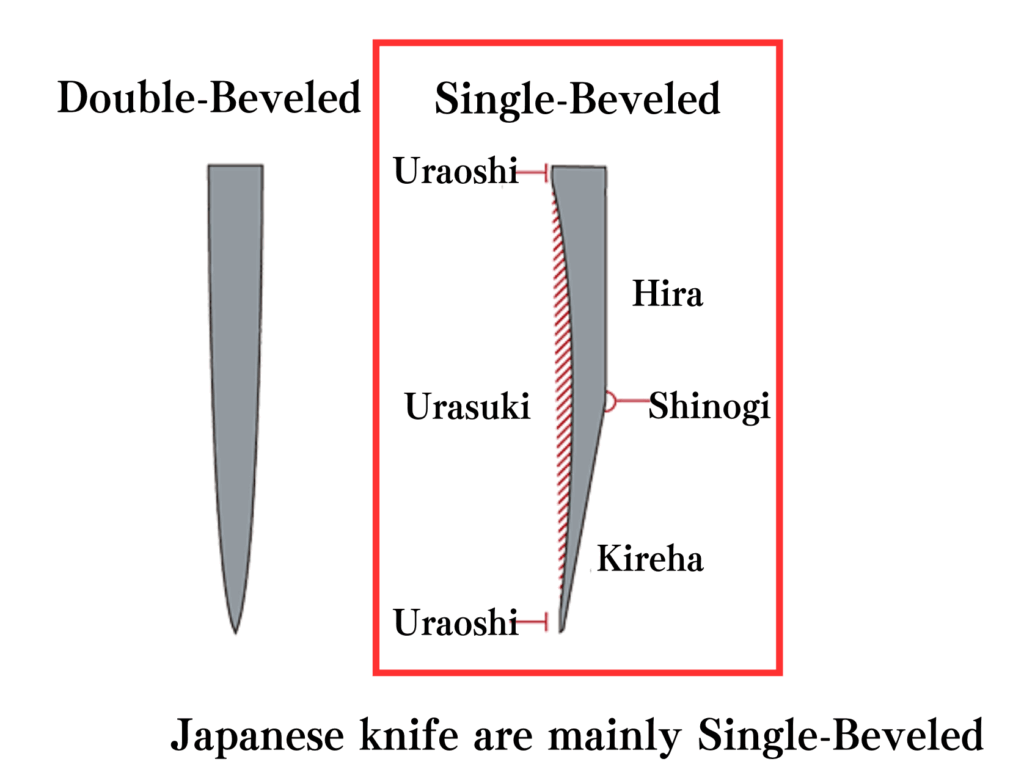

Japanese Knives Are Single-Beveled

Some unique parts of a single-bevel Japanese knife, as noted above, include:

- Shinogi (鎬) – The ridge line where the primary bevel meets the blade face. The shinogi influences the knife’s strength, sharpness, and balance. A well-defined shinogi line helps guide precise sharpening at the correct angle.

- Hira (平) – The broad, flat side of the blade’s front face. This flat surface keeps the knife stable in use and contributes to an even, clean cut. It also allows accurate sharpening on the front side of the blade.

- Urasuki (裏スキ) – A gentle hollow grind on the back side of the blade. This concave surface reduces friction and contact with food, resulting in smoother slicing and preventing food from sticking to the blade. (This feature is especially important for sashimi knives to pull through fish in one smooth motion.)

- Uraoshi (裏押し) – A narrow flat rim along the back edge of the blade. When sharpening, this small flat area acts as a guide to help maintain a consistent angle. It improves stability during sharpening and ensures the delicate back hollow (urasuki) is preserved.

Thanks to this single-bevel construction, Japanese knives can be sharpened to a more acute, razor-like edge than most double-edged knives. They excel at precision cutting techniques that are important in Japanese cuisine – for example, slicing fish for sashimi into paper-thin pieces or performing intricate decorative vegetable cuts for garnishes.

Additionally, the hollow back (urasuki) on a single-bevel blade reduces drag, and the one-sided edge creates an exceptionally smooth cutting face. As a result, the cut surface of food tends to be very clean, and ingredients are less likely to cling to the blade. This makes single-bevel knives ideal for slicing tasks (like cutting sashimi or sushi) where a clean cut and easy release of food are desired.

Single-bevel knives also offer superb control. The asymmetrical edge causes the blade to gently pull in one direction as it cuts. In the hands of a skilled user, this tendency can be exploited to guide the knife along a very precise line, making accurate cuts exactly where intended.

However, there are some drawbacks to the single-bevel design. First, traditional single-bevel knives are typically made for right-handed users – a left-handed person would need to obtain a special left-handed version of the knife. These left-handed models exist but are less common and often must be custom ordered.

Secondly, sharpening and maintenance of a single-bevel knife is more demanding. It requires specialized skill to sharpen the blade correctly, keeping the uraoshi and urasuki intact. Improper sharpening (for example, grinding the back flat incorrectly) can ruin the blade’s geometry, dulling the knife and negating its unique cutting advantages. In short, single-bevel knives are best suited to experienced users or professionals who can care for them properly.

It’s worth noting that not all Japanese knives are single-beveled. There are popular double-bevel Japanese knives as well – for instance, the gyuto (Japanese chef’s knife) and santoku (multipurpose knife) are both double-edged. Home cooks in Japan often use these double-bevel knives for general-purpose cutting, while reserving the single-bevel blades for very specialized tasks.

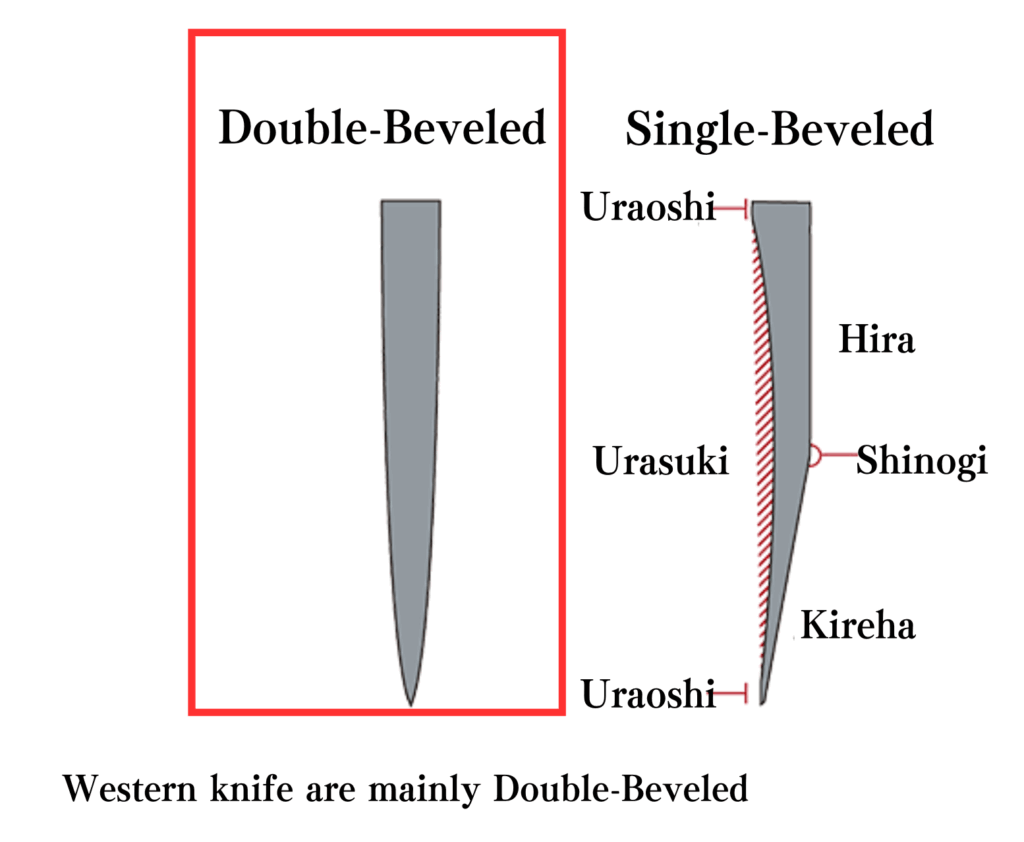

Western Knives Are Double-Beveled

A double-bevel knife (両刃, ryōba) has both sides of the blade sharpened in a symmetrical V-shape. This is the standard blade geometry in Western culinary tradition (Europe, Americas, etc.). In cross-section, a double-bevel blade shows two equal angles meeting at the cutting edge, meaning the edge is centered along the blade’s thickness.

Because both sides of the blade are honed at similar angles, Western knives can be used comfortably by either right-handed or left-handed cooks. The knife’s balance is typically down the middle, which makes straight cuts very stable. The centered edge and thicker spine also make it easier to perform techniques like rocking chops, push cuts (pressing straight down through food), or quick dicing with minimal deviation.

This design is particularly well-suited for tougher cutting tasks. A double-bevel knife can handle cutting through bone-in meats or dense vegetables more easily than a delicate single-bevel knife. For example, chopping up a whole chicken or cubing a large pumpkin is usually safer and more efficient with a sturdy double-bevel Western knife.

Another advantage is ease of maintenance. Sharpening a double-bevel knife is relatively straightforward – you simply sharpen both sides at the appropriate angle. There are no special back-side features to worry about, so maintaining a sharp edge can be done with standard kitchen sharpeners or whetstones. Day-to-day home care is more forgiving, as you can quickly touch up the edge without specialized technique.

On the other hand, a double-bevel knife cannot match the sheer finesse of a single-bevel blade for ultra-precision tasks. The edge angle is slightly wider, and there’s no hollow back, so it’s harder to achieve paper-thin slices or the ultra-clean cuts required for expert sashimi and intricate garnish work. In practice, this means a Western knife is less optimal for things like translucent sashimi slices or elaborate vegetable carving – it can certainly do these tasks, but not with the same ease and perfection that a finely tuned Japanese knife can.

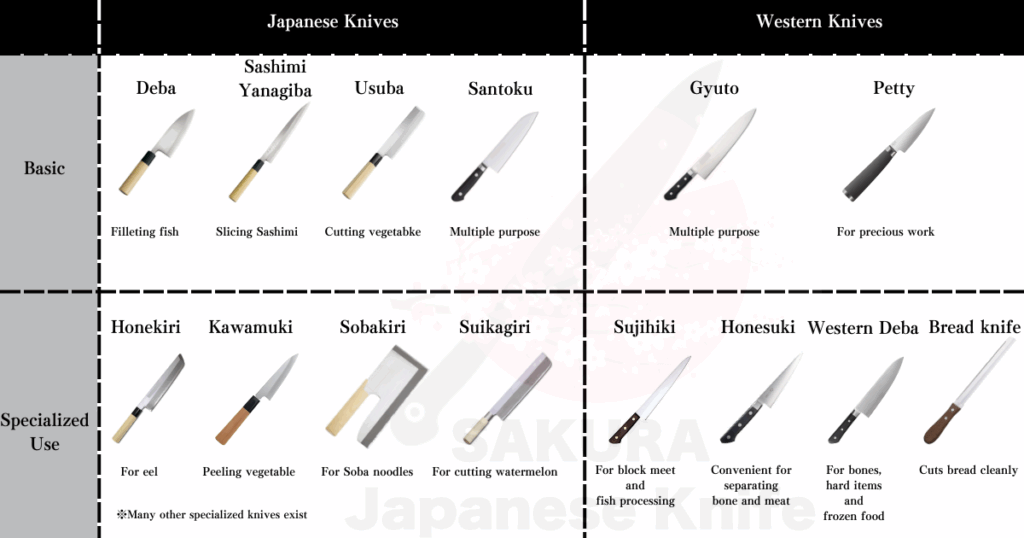

Variety of Knife Types and Uses

Japanese cuisine places a strong emphasis on delicate knife work and showcasing the natural flavor and texture of ingredients.

Consequently, traditional Japanese knives come in a wide variety of specialized types, each designed for a particular purpose or ingredient.

In professional Japanese kitchens, chefs often switch between different knives for different tasks to achieve the best results. (In home cooking, people may rely on just one or two all-purpose knives like the santoku, but professionals maintain an extensive set of blades.)

Below are some common types of Japanese knives and their typical uses:

- All-Purpose: Santoku (literally “three virtues”) – a multipurpose kitchen knife used for chopping meat, fish, and vegetables; Nakiri – a rectangular knife specifically for slicing and chopping vegetables.

- Fish Preparation: Deba – a heavy, thick knife for butchering and filleting fish (can cut through fish bones); Mioroshi deba – a thinner fillet knife combining aspects of deba and sashimi knife for cleaning fish; Ajikiri – a small knife for cleaning small fish like horse mackerel (aji); Kaisaki – a short knife for opening and preparing shellfish.

- Sashimi Slicing: Yanagiba – a long, slender sashimi knife used to slice raw fish in one pull for pristine slices; Sakimaru takobiki – a variation of sashimi knife with a rounded tip (often used in the Kansai region); Kiritsuke – a hybrid knife with a K-tip used by experienced chefs for slicing fish and vegetables (combines functions of yanagiba and usuba); Takobiki – a sashimi knife with a squared tip used in the Kanto region, ideal for slicing octopus (tako).

- Vegetables: Usuba – a traditional single-bevel vegetable knife with a straight edge for ultra-thin vegetable slicing; Kama-usuba – an usuba with a sickle-shaped tip for decorative cutting; Kawamuki – a small peeler knife for shaving skins (often used for peeling vegetables or fruits).

- Specialty Knives: Hamokiri – a long knife for cutting open hamo (pike conger eel) and other fish with many fine bones; Sobakiri – a cleaver-like knife for cutting soba noodles to uniform width; Suikakiri – a large knife for slicing watermelons and big melons; Chinese cleaver (Chūka bochō) – a broad, rectangular cleaver adopted from Chinese cuisine for chopping and slicing; Sushikiri – a knife for cutting sushi rolls cleanly without squashing them; Unagi-saki – an eel filleting knife (Kansai style) used to split and bone eel from the belly side; Edo-saki – an eel filleting knife (Kanto/Tokyo style) used to fillet eel from the back.

By contrast, Western cooking culture tends to rely on a smaller set of versatile knives that can handle many different foods. It is common in Western kitchens to use one knife for multiple tasks, so the knives are designed to be more all-purpose. The classic Western chef’s knife (called a gyuto in Japanese when made in that style) and the smaller petty knife cover most needs, from carving a roast to chopping herbs.

Common Western-style knives include:

- Chef’s Knife (Gyuto): The primary all-purpose kitchen knife, typically 8–10 inches long, used for slicing, dicing, and chopping a wide variety of ingredients.

- Petty Knife: A small utility knife (similar to a paring or trimming knife) for precise work like peeling, trimming fat, or slicing small fruits.

- Sujihiki (Carving Knife): A long, slender slicing knife for carving cooked meats or filleting fish (Western equivalent of a carving or fillet knife).

- Honesuki (Boning Knife): A stout, triangular boning knife used to debone poultry and break down meat cuts; its pointed shape and stiffness make it easy to work around bones and joints.

- Yo-deba (Western Deba): A heavy-duty Western version of the deba – a thick, robust knife for cutting through poultry bones or portioning large fish and meat. (This is essentially a Western-style butcher knife.)

- Bread Knife: A long serrated knife used for slicing bread, pastries, and other foods with a hard crust and soft interior.

Differences in Materials and Manufacturing

Difference in Carbon Content

One key distinction between Japanese and Western blades is the type of steel.

Japanese knives typically use high-carbon steel with a higher carbon content, while Western knives tend to use stainless steel (alloy) with lower carbon content.

High-carbon steel is harder and can be honed to an extremely sharp edge that stays sharp for a long time, but it is also more brittle and prone to corrosion.

This means Japanese knives can chip if misused and will rust if not properly maintained. Western stainless steels, on the other hand, are softer (less hard) and generally cannot hold quite the same razor-fine edge, but they are far more rust-resistant and forgiving when it comes to maintenance and use.

Differences in Manufacturing Techniques

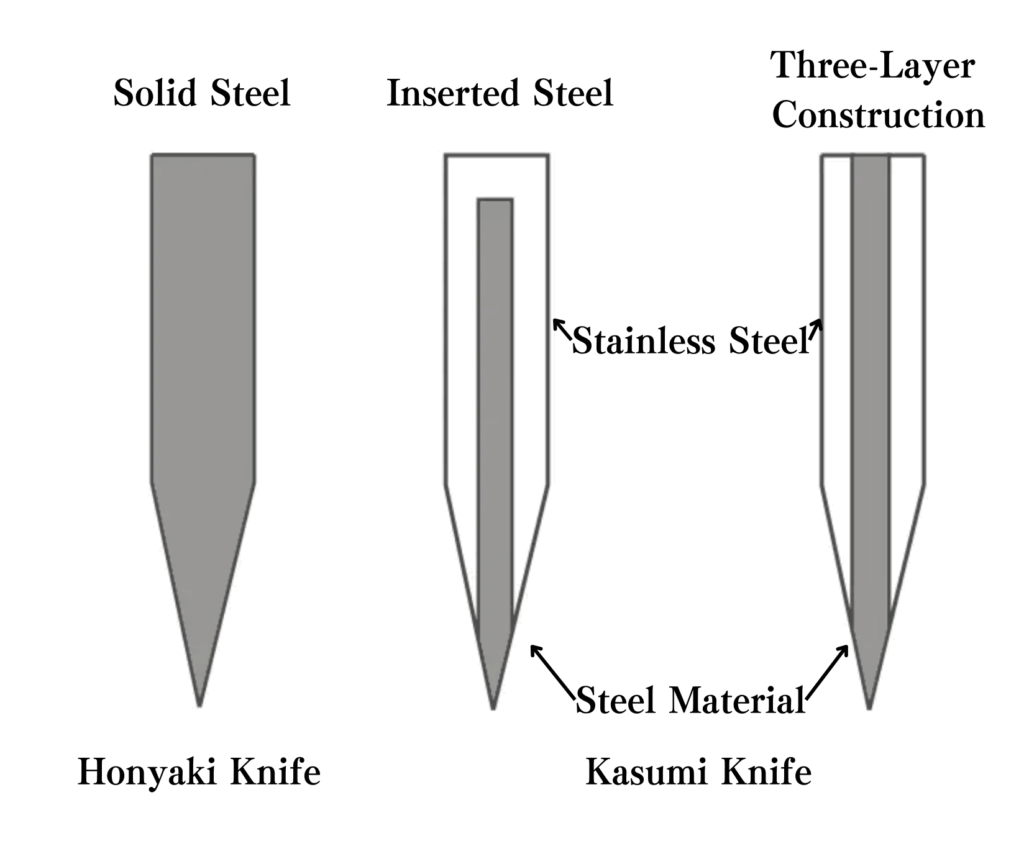

Japanese knifemaking encompasses two major traditional methods: honyaki and kasumi. A honyaki knife is forged from a single piece of high-quality steel (a “full steel” construction).

It undergoes elaborate heat treatment (similar to the process for forging samurai swords), resulting in a blade of very high hardness and cutting performance.

A kasumi knife, by contrast, is made by laminating a hard steel core with softer steel or iron on the outside.

In other words, the cutting edge is hard steel, but the body of the knife is reinforced with a more pliable jacket material. This is achieved with techniques like wari-komi (wrapping a hard core in a soft iron cladding) or san-mai (sandwiching the hard steel between two outer layers).

The characteristics of honyaki vs. kasumi blades can be compared as follows:

| Aspect | Honyaki (Full Steel) | Kasumi (Clad Steel) |

|---|---|---|

| Construction & Features | Forged entirely from one piece of high-grade steel. Traditionally water-quenched and tempered like a Japanese sword, achieving extremely high hardness and a keen edge. | Constructed by combining a hard carbon steel core with a softer iron or steel outer layer (e.g. by wrapping or sandwich forging). This laminated structure offers a hard cutting edge supported by a softer spine. |

| Advantages | Can attain an extremely sharp edge with excellent edge retention when properly sharpened. | Less prone to chipping or breaking due to the supportive soft layer. Often easier to sharpen and more forgiving to use, and typically not as expensive as honyaki knives. |

| Disadvantages | Expensive and difficult to produce (requires master craftsmanship and high-grade steel). Because the blade is very hard throughout, it can chip or crack if mishandled and is more susceptible to rust without diligent care. | Does not reach the absolute extreme hardness or razor edge of a honyaki blade (the very hardest steel); edge retention is slightly lower. However, it still offers outstanding sharpness and durability for practical use. |

| Best Suited For | Professional chefs and specialists; those who require maximum performance and can maintain it meticulously. | General use by both professionals and home cooks; ideal for those who want high performance with easier maintenance and lower cost. |

(In contrast, Western knives are almost always made from a single piece of steel — essentially a mono-steel construction — which keeps their manufacturing process straightforward.)

Handle Differences

Japanese knife handles are generally made from lightweight woods like magnolia.

They often have unique cross-sectional shapes such as a D-shape, octagon, or round profile that fit comfortably in the hand. The blade’s tang is usually a partial tang that is inserted into the handle (a friction fit, often reinforced with a horn or plastic ferrule at the bolster). This construction keeps the knife very lightweight overall and gives it a nimble, delicate balance favored for precise cutting techniques.

Western knife handles, on the other hand, are typically made from harder, durable materials like plastic, pakkawood (layered resin-impregnated wood), or composite materials.

Most Western handles use a full-tang design – the metal tang of the blade runs through the entire handle and is often riveted in place between handle scales. Western handles tend to be thicker and have a symmetric shape (oval or rounded rectangle in cross-section), which provides a solid, comfortable grip for heavier chopping motions.

The weight of a full tang and denser handle material adds stability and durability to the knife. Overall, the lighter wa-handle lends itself to finesse and agility, whereas the heavier Western handle allows for more power and robustness in cutting.

(Because of these differences, Japanese knives excel at controlled, delicate cuts, while Western knives let you apply more force for heavy-duty tasks.)

Maintenance Differences

Usage Environment & Handling

Due to their hard, thin edges, Japanese knives are somewhat delicate in use. You should avoid using a wa-bocho on very hard items – for example, cutting through frozen food or bones with a fine-edged Japanese knife can cause the blade to chip or crack.

It’s important to use these knives for the intended soft or medium-hard ingredients and employ proper technique (no twisting or prying with the blade). Handle them gently and let the sharp edge do the work with minimal force.

By contrast, Western knives are engineered to be tougher and more tolerant of less careful use.

A good Western chef’s knife can withstand chopping through chicken bones or hard squash without as much risk of damage to the edge. They are less likely to chip with casual use, and in general they don’t require the same level of caution.

While you still shouldn’t abuse any quality knife, a Western knife will forgive the occasional misuse more than a brittle Japanese knife. Also, many Western knives are advertised as dishwasher-safe or generally easy to care for (though it’s still best to hand wash and dry them, especially high-end ones).

The care guidelines for Western knives are typically more relaxed compared to the strict precautions often recommended for carbon steel Japanese blades.

Daily Rust Prevention

When it comes to preventing rust (錆, sabi), the differences between Japanese and Western knives are significant. Most Japanese knives are made of high-carbon steel, which is not stainless.

This means they can rust or discolor easily if not properly cared for. To prevent rust, you should always wash and thoroughly dry a Japanese knife immediately after use.

Never leave a carbon steel knife sitting with water or moisture on it, or it will quickly develop rust spots and the edge will degrade. It’s a good practice to wipe the blade during use if it’s cutting something wet, and to store it dry in a protective sheath or knife block.

Western knives, in contrast, are usually made from stainless steel alloys that are formulated to resist rust. They can handle a bit more neglect in terms of moisture.

Of course, you should also dry your Western knives after washing to maintain them in top condition, but they won’t rust at the mere sight of water like a carbon steel blade might.

In practical terms, you don’t have to be as anxious about rust with Western knives – they are lower maintenance in this regard, which is one reason they’re popular in busy home and restaurant kitchens.

Sharpening and Blade Care

Maintaining the edge is another area of difference. Japanese knives need to be sharpened periodically using whetstones to preserve their legendary cutting performance.

Because their steel is very hard and can take an exceptionally sharp edge, you’ll want to sharpen them with fine grit stones to keep that razor edge.

This typically means learning to use waterstones and spending time to hone the single-bevel or carefully maintain the double-bevel angle (depending on the knife). The payoff is that a well-sharpened Japanese knife will glide through ingredients effortlessly.

However, it does require a bit of skill and dedication to consistently sharpen these knives by hand and to avoid altering their intended blade geometry.

Western knives are generally easier to sharpen and maintain for the average user. The slightly softer stainless steel can be sharpened with a variety of tools – if you’re not comfortable with whetstones, you can use pull-through sharpeners or honing rods and still get a decent edge.

Western knives typically don’t need to be taken to an extremely high degree of sharpness for everyday cooking, so a quick touch-up is often sufficient. They can also tolerate more aggressive sharpening techniques (like electric sharpeners) without much risk. In short, routine maintenance of a Western knife is more straightforward, whereas Japanese knives reward more specialized care and skillful sharpening.

Summary

To recap, below is a quick comparison of Japanese vs Western kitchen knives:

| Aspect | Japanese Knives | Western Knives |

|---|---|---|

| Blade Design | Mostly single-bevel edge (sharpened on one side) | Mostly double-bevel edge (sharpened on both sides) |

| Knife Types | Many specialized types for specific tasks (highly varied by use) | Fewer types; emphasis on versatile, multi-purpose knives |

| Blade Material | Hard high-carbon steel (extremely sharp edge, but can rust/chip) | Stainless steel or softer alloy (resists rust, more durable but slightly less sharp) |

| Construction | Both full-steel (honyaki) and laminated (kasumi) traditional constructions are used | Generally a single piece of steel (mono-steel) construction for most blades |

| Maintenance | Requires careful upkeep (keep dry, sharpen properly; blade is less forgiving) | Easier upkeep (more rust-resistant and robust; simple sharpening and care) |

Both Japanese and Western knives have their own strengths. Ultimately, the best choice is a knife (or knives) that fit your cooking style and the tasks you most often perform.

You might even choose to use both: for example, a sturdy Western chef’s knife for heavy work and a precise Japanese knife for detail work. By understanding the differences outlined above, you can make an informed decision and appreciate the unique qualities of each style.

Comments