Many cooking enthusiasts have heard of the Kiritsuke knife yet wonder: “When should I use a Kiritsuke? How is it different from a regular chef’s knife or a Santoku? Is it like a Deba or Yanagiba?”

If you’re curious about the Kiritsuke, you’re not alone. In fact, the Kiritsuke is a somewhat legendary Japanese knife – traditionally reserved only for top chefs – that combines the functions of several specialized knives into one.

It’s a unique hybrid blade that can handle tasks from filleting fish and slicing sashimi to delicate vegetable carving, earning it a reputation as an “all-rounder” in Japanese cuisine.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore what a Kiritsuke knife is (including its meaning and pronunciation), the benefits and drawbacks of using one, and how it compares to other knives like the Gyuto (chef’s knife), Santoku, and Bunka.

We’ll also provide practical tips on how to use a Kiritsuke properly and safely, plus insights into modern variations (such as double-bevel Kiritsuke knives and stainless steel models) that make this traditional blade more accessible to home cooks.

Whether you’re a beginner curious about Japanese knives or an intermediate home cook looking to expand your cutlery skills, this article will equip you with everything you need to know about the Kiritsuke knife. Let’s dive in!

What is a Kiritsuke Knife? (Meaning, Origin & Characteristics)

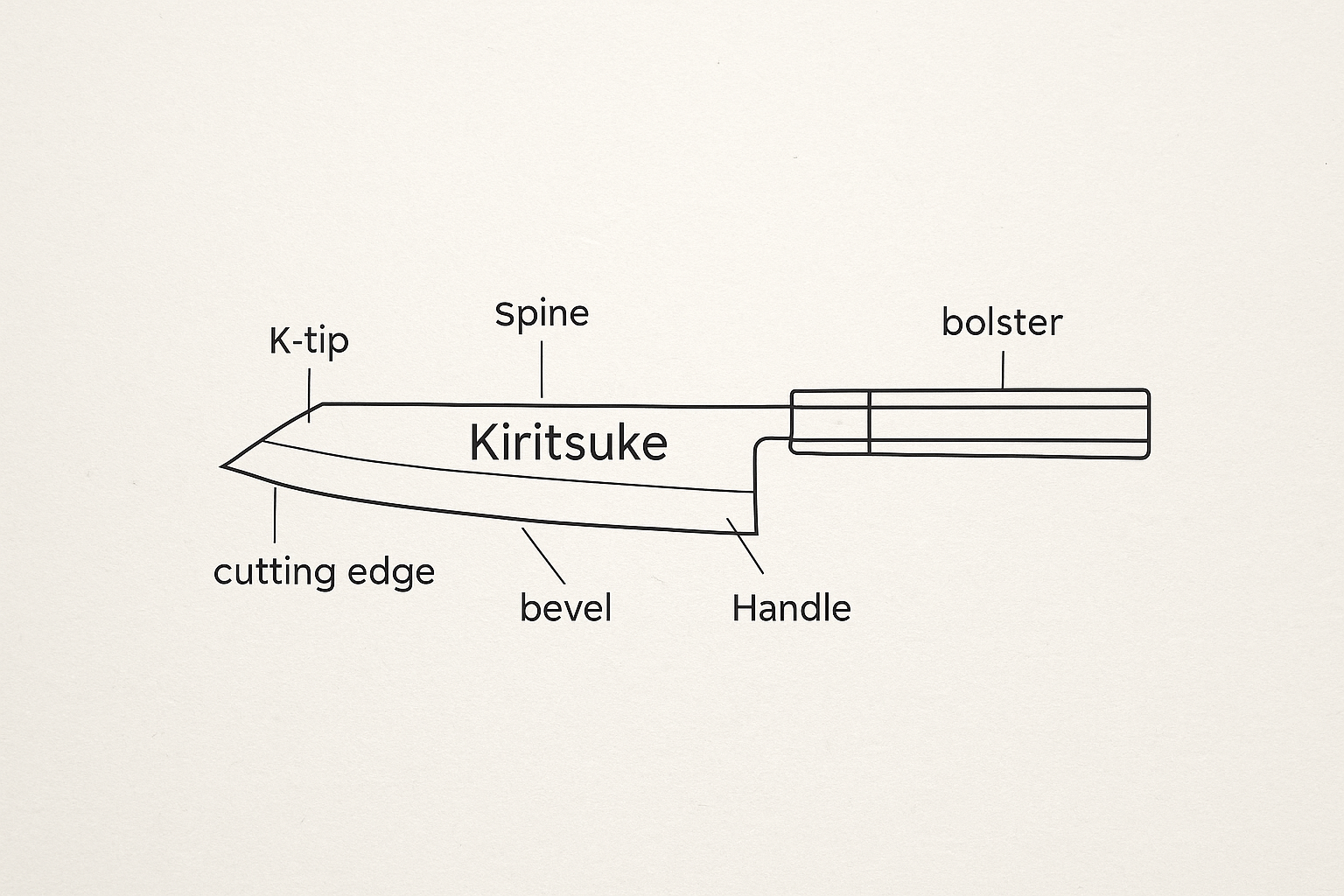

Kiritsuke (切り付け包丁, Kiritsuke-bōchō) is a type of traditional Japanese kitchen knife known for its distinctive long, flat blade and sharply angled tip.

The term “Kiritsuke” literally means “to slit open” in Japanese, a fitting name given its ability to slice through ingredients with ease. Pronounced roughly as “kee-ree-tsu-keh”, this knife is sometimes nicknamed the “chef’s sword” because of its elegant, katana-like appearance and status.

In Japanese, boōchō (包丁) simply means “kitchen knife,” so “Kiritsuke-bōchō” refers to this specific style of knife.

Blade Length and Shape:

A classic Kiritsuke typically has a blade length of about 240 mm to 330 mm (9.5–13 inches), making it longer than many Western knives.

The blade is slender yet substantial, often as thick as a heavy-duty knife near the spine. Its defining feature is the “K-tip” or clipped reverse tanto point – the spine angles down to meet the edge in a sharp, sword-like tip rather than a curved point.

This angled tip (called kengata) provides an additional cutting edge at the tip and gives the knife a striking profile. The cutting edge of a Kiritsuke is typically very straight or only slightly curved, resembling the flat profile of a vegetable knife. This flat belly is excellent for push-cutting and pull-cutting, though it means the Kiritsuke isn’t designed for rocking motions (more on technique later).

Hybrid Design – Two Knives in One:

The Kiritsuke was originally designed as a hybrid of two specialized Japanese knives – the Yanagiba and the Usuba.

The Yanagiba is a long, narrow sashimi knife used for slicing raw fish in clean strokes, while the Usuba is a tall, flat vegetable knife used for precise peeling and chopping.

The Kiritsuke combines elements of both: it has the length and razor-sharp edge of a Yanagiba (ideal for slicing fish) and the height and straight edge of an Usuba (useful for chopping and paper-thin veggie cuts).

In essence, the Kiritsuke can be used like an Usuba for vegetables or like a Yanagiba for fish, making it one of the rare traditional Japanese knives that is truly multi-purpose. Some chefs even liken it to blending the Deba (a heavy fish butchery knife) with the Yanagiba – it carries enough backbone to cut through fish bones like a Deba, yet retains a thin, fine edge for slicing as a Yanagiba would.

Single-Bevel Edge:

Traditionally, Kiritsuke knives are single bevel blades.

This means they are sharpened on one side only (usually the right side for right-handed users), with the other side of the blade left flat or slightly hollow-ground.

A single-bevel edge can achieve extremely fine sharpness and very precise, straight cuts (great for things like sashimi), but it also requires skill to use and sharpen. Because of this design, classic Kiritsuke knives were considered professionals’ tools – in fact, in many Japanese kitchens only the executive chef was allowed to use the Kiritsuke as a symbol of status and expertise.

A single-bevel Kiritsuke in the wrong hands can be unforgiving (it may steer or dig in if not guided correctly), which is why historically it was reserved for the most senior chef.

Modern Double-Bevel Versions:

These days, you’ll also encounter double-bevel Kiritsuke knives, sometimes labeled as “Kiritsuke Gyuto” or “K-tip Gyuto.”

Technically, a double-bevel Kiritsuke is a Western-style chef’s knife (gyuto) that adopts the Kiritsuke’s signature shape – i.e. a gyuto with a K-tip and a relatively flat edge. Many Japanese knife makers produce this hybrid to offer the look of a Kiritsuke with the ease of use of a double-edged knife. We’ll discuss these modern variations in detail later, but in short: double-bevel Kiritsuke knives are more user-friendly for beginners and left-handed users, since they cut evenly on both sides like a normal chef’s knife.

In summary, the Kiritsuke is a long, flat-edged Japanese knife with an angled tip, traditionally single-edged and meant to perform tasks usually divided between separate knives (slicing fish and chopping vegetables). It’s a beautiful tool but comes with a pedigree – historically a “master’s knife” used only by highly skilled chefs. Next, let’s look at why this blade is so unique and what you can actually do with it.

Why is the Kiritsuke Unique? The “All-Rounder” Capabilities of its Angled Tip

The Kiritsuke has earned a reputation as an “all-rounder” knife in Japanese cuisine – a blade that can cover multiple tasks in one. This uniqueness largely comes from its sharp angled tip (the kakugata or “K-tip”) and the blend of characteristics we discussed. Let’s break down what that means in practical use.

Multi-Purpose Functionality:

Unlike most traditional Japanese knives which are highly specialized (one for chopping vegetables, another for filleting fish, another for slicing sashimi, etc.), the Kiritsuke can handle several of these jobs reasonably well. It’s often described as having the “best of both worlds” from the Yanagiba and Usuba.

For example, you can use a Kiritsuke to fillet and portion a fish (including cutting through small bones), then clean the same fish into neat sashimi slices, and even do fine decorative cuts on garnishes – all with the same knife. This versatility is extremely convenient if you want to minimize swapping knives mid-prep or if you’re working in a tight space with room for only one specialty blade.

Thick Spine for Power, Thin Edge for Precision:

A traditional Kiritsuke often has a sturdy spine and some heft, akin to a Deba (fish butcher knife), which means it can apply force to cut through fish heads or cartilage in a pinch. At the same time, its edge is honed thin and sharp like a Yanagiba, so it slices cleanly without tearing delicate foods.

This dual nature lets it tackle both heavy and delicate tasks to an extent. For instance, it might not be as heavy as a true Deba for chopping through large bones, but it’s heavy-duty enough for small-to-medium fish. Conversely, it might not be as surgically thin as a Yanagiba for ultra-long sashimi cuts, but it’s precise enough for most slicing tasks. It’s this balanced compromise that makes the Kiritsuke special.

The Angled Tip (“K-tip”) Advantage:

One of the Kiritsuke’s greatest assets is that pointed, angular tip. This clipped tip acts almost like a small secondary knife at the end of the blade. You can use the sharp point and the short straight section of edge near the tip for tasks that require precision or a narrow blade insertion.

Chefs often use the Kiritsuke’s tip to score proteins or veggies – for example, making small incisions in fish to help it cook evenly, or cutting a crosshatch pattern in an eggplant or mushroom for decoration. The tip’s acute angle allows it to pierce and cut with surgical precision, in ways a rounded tip knife might struggle with.

YANAGAWA

YANAGAWAYANAGAWA (Sushi Chef): “This angular tip is surprisingly useful — whether I’m skinning a flounder fillet or adding tiny decorative cuts, it’s like my fingertips extend right through the tip of the knife.“

In other words, the Kiritsuke’s tip gives you incredible control for fine work, almost as if it were an extension of your hand. Yanagawa’s experience as a sushi chef highlights how intuitive and sensitive a Kiritsuke can feel when doing detail work like peeling fish skin or carving garnish.

Flat Edge for Clean Slices:

The mostly straight edge of the Kiritsuke means that when you slice or push-cut, the entire length of the blade contacts the cutting surface at once. This is excellent for getting even, clean cuts (for example, making uniform slices of a radish or fillet).

There’s no rocking motion needed (in fact, rocking is discouraged with this knife); instead, you either push the blade forward or pull it back in one smooth motion to cut. This technique, combined with the sharpness of a single-bevel edge, lets you slice through foods without cracking or squashing them.

For instance, when cutting something soft like tofu or a ripe tomato, a Kiritsuke can glide straight down and produce a neat cut with minimal deformation to the food.

Efficient for Multiple Steps:

Think of a scenario in Japanese cooking – say you caught a fresh fish and want to prepare it nose-to-tail. With a Kiritsuke, you could use the back end of the blade (near the handle) and the thickness of the spine to cut through small bones and remove the fish head, much as you would with a Deba.

Then, use the middle of the blade to filet the fish, sliding along the backbone. Next, use the front part of the blade to slice the fillet into sashimi pieces – the straight, long edge works almost like a shorter yanagiba for drawing through the flesh. Finally, perhaps you want to add a decorative cut to a vegetable for the plate garnish – the tip of the Kiritsuke lets you carve with precision, maybe creating a chrysanthemum carrot or scoring a cucumber.

All of these steps can flow one after another with the same knife. In a professional setting, this can save time; in a home setting, it’s simply satisfying (and fewer knives to wash!).

Kiritsuke vs Gyuto (Japanese Chef’s Knife): What’s the Difference?

One common comparison is Kiritsuke vs Gyuto. The Gyuto is the Japanese equivalent of a Western chef’s knife – a versatile, double-edged knife used for cutting meat, vegetables, and fish. At first glance, an inexperienced eye might confuse a Kiritsuke with a Gyuto since both can be general-purpose. However, they have distinct differences in shape, edge, and ideal usage. Here’s a side-by-side breakdown of Kiritsuke vs Gyuto:

As the table above shows, the Kiritsuke and Gyuto serve different philosophies. If your cooking is heavily Japanese-influenced (lots of fish, emphasis on precision and presentation) and you’re comfortable with traditional knives, a Kiritsuke can be a fascinating, enjoyable tool. It brings a touch of “和 (wa) spirit” to your kitchen with its look and cutting feel. On the other hand, if you want one knife to cover a broad range of tasks including hearty Western-style chopping and you value ease of use, a Gyuto is generally more practical. In many cases, the decision comes down to your personal cooking style and how much you value the Kiritsuke’s specialized charm over the Gyuto’s general-purpose convenience.

To illustrate, consider these scenarios:

- “I often cook whole fish and also do decorative vegetable plating for Japanese dishes.” – A Kiritsuke might be a perfect companion, letting you break down fish and finesse garnishes with one blade.

- “I primarily need a knife for slicing raw fish for sashimi and some light vegetable work, but I already have heavy knives for butchery.” – A Kiritsuke shines in this role, as it was practically made for those tasks.

- “I need to cut up chickens, dice onions, slice steaks, and occasionally mince herbs – and I don’t do much sashimi.” – A Gyuto will handle all that with ease, whereas a Kiritsuke would not be ideal for heavy meat butchery or continuous rock chopping of herbs.

- “I’m a knife collector or enthusiast.” – You might actually own both! Use the Gyuto for everyday generic tasks, and take out the Kiritsuke for when you’re in the mood to do something special or practice Japanese knife skills.

GENSAKU (Bladesmith): “Think of the Kiritsuke as a specialist that can multitask, whereas a Gyuto is a true generalist. If you already have a Yanagiba and a Deba and use them regularly, you might not need a Kiritsuke. But if you’re looking to add flexibility to your fish work without juggling knives, the Kiritsuke is a trusty ally.”

This aligns with common advice: “魚の骨を丁寧に処理したい” (If you want to handle fish bones carefully) and “刺身や飾り切りをもっと本格的に” (make sashimi and decorative cuts more authentic), then Kiritsuke is for you. But if you just need an all-around knife that covers meat and veg day-to-day, go with a Gyuto.

Next, let’s compare the Kiritsuke to a couple of other popular Japanese knives that home cooks often ask about.

Kiritsuke vs Santoku: Which Knife for Everyday Use?

Another common comparison is Kiritsuke vs Santoku. The Santoku is one of the most popular Japanese knives in home kitchens. Its name means “three virtues” – referring to slicing, dicing, and mincing – the three tasks Santokus excel at. A Santoku is essentially Japan’s answer to a multipurpose chef’s knife, usually shorter and more compact than a Gyuto, with a distinct sheep’s foot (curved-down) tip.

So, how does our specialized Kiritsuke stack up against the do-it-all Santoku?

Size and Shape:

Santoku knives are generally shorter and taller than Kiritsuke knives. A typical Santoku ranges from about 5 to 7 inches in blade length (approximately 130–180 mm), whereas a Kiritsuke is longer, about 8 to 10+ inches (240–270+ mm). The Santoku has a wide blade that is nearly as tall as a chef’s knife, with a blunted sheepsfoot tip (the spine curves downward to meet the edge, rather than forming a sharp point). In contrast, the Kiritsuke has a narrower blade height and a sharply angled point.

The cutting edge of the Santoku is often a gentle curve toward the tip but mostly straight, enabling an up-and-down chopping motion. Both Santoku and Kiritsuke have relatively flat profiles compared to a Western knife, but the Santoku’s front end curves down instead of coming to a k-tip point.

Bevel and Edge:

Santokus are double-bevel (double-edged) knives. This makes them ambidextrous and easy to sharpen for most users. Kiritsuke knives, as noted, are traditionally single-bevel (though double-bevel versions exist). This gives the Santoku an immediate edge in user-friendliness – you don’t need specialized knowledge to use a Santoku effectively right out of the box.

Intended Use:

The Santoku is truly a general-purpose knife. Home cooks grab it for chopping vegetables, slicing meats, cutting fish fillets, you name it. It’s adept at the “three virtues” tasks: slicing, dicing, mincing all kinds of ingredients. Its broad blade also makes it easy to scoop up chopped food and transfer from board to pan (a small quality-of-life perk).

The Kiritsuke, while versatile within the context of Japanese cuisine, is a bit more specialized in practice. It shines at fish and vegetable prep particularly, but you wouldn’t typically use a Kiritsuke to, say, rapidly mince a bunch of parsley or butcher a chicken into parts – tasks where a Santoku or Gyuto would be more comfortable. In short, Santoku = everyday all-purpose; Kiritsuke = specialty all-purpose (focused on Japanese tasks).

Ease of Use:

Santoku knives are often recommended for beginners or everyday cooks because of their shorter length and easy handling. They feel nimble and safe, partly due to the lack of a sharp tip (less chance of accidental piercing) and the manageable size for those who find long blades intimidating.

The Kiritsuke, being longer and usually single-beveled, can be trickier. It requires a bit more technique to control, especially during long slicing motions or when cutting straight down without wedging. Also, the Kiritsuke’s very sharp tip, while an advantage for certain cuts, demands respect to avoid poking through cutting boards or ingredients unintentionally.

Cutting Technique Differences:

With a Santoku, many cooks utilize a down-and-forward “push cut” or a slight rocking motion (though the Santoku’s curve is not as pronounced as a Western knife for rocking). The flat profile encourages a push cut – much like the Kiritsuke, actually. So in terms of technique for chopping veggies, a Santoku and a Kiritsuke (if double bevel) aren’t vastly different: both prefer a forward-backward motion over rocking.

However, when mincing (e.g. herbs or garlic), Santoku users often do a quick up-and-down chop or light rock because the tip is not pointed. Kiritsuke users, on the other hand, will stick to drawing the blade or pushing it; the Kiritsuke doesn’t rock well at all due to its completely flat edge.

And for slicing proteins (like making thin slices of meat or fish), a Kiritsuke’s draw-cut technique is akin to using a yanagiba – you pull the blade toward you in one clean sweep. A Santoku can slice meat too, of course, but if the piece is large, its shorter length means you might need a see-saw motion or multiple strokes to get through.

Versatility vs Precision: Here the Santoku wins on versatility in a Western kitchen context – it can handle a wider variety of tasks (including ones like cutting cheese, slicing bread in a pinch, or trimming meat) fairly well. The Kiritsuke wins on precision for certain tasks – for instance, when cutting a daikon radish into thin sheets or filleting a fish, the Kiritsuke’s form and single bevel can achieve more delicate, precise results than a Santoku would. It’s a bit of a trade-off: Santoku gives you breadth of use and ease; Kiritsuke gives you finesse and specialization.

- If you need a daily driver knife for general cooking (Japanese and non-Japanese foods alike) and you’re not specifically focused on traditional techniques, a Santoku is likely the better choice. It’s forgiving, handy, and still provides a very sharp Japanese blade experience. Many home cooks adore Santokus for their comfort and reliability.

- If you’re a Japanese cuisine enthusiast who often fillets fish or wants to practice sushi/sashimi presentation, and you’re willing to invest time in learning, a Kiritsuke offers capabilities the Santoku doesn’t (like perfectly smooth sashimi slices or intricate cuts with the tip). It could complement your knife collection alongside perhaps a Gyuto or Santoku for other tasks.

Remember, these knives can coexist. It’s not uncommon for a kitchen to have a Santoku or Gyuto as the workhorse and a Kiritsuke as the specialist for certain dishes.

YUKIKO (Home Chef): “I love my Santoku for everyday chopping – it’s like an extension of my hand when I’m quickly prepping dinner for the kids. But when I have a beautiful piece of fish or want to be artistic with presentation, I reach for a Kiritsuke. It forces me to slow down and be more deliberate, almost like I’m channeling a sushi chef spirit!”

Her comment highlights a key difference in mindset: a Santoku is often about efficiency and comfort, whereas using a Kiritsuke can feel like an experience or craft in itself. Neither is objectively “better” – it depends on what you value in your cooking routine.

Kiritsuke vs Bunka: Two Knives with K-Tips – Which Is For You?

At first glance, a Kiritsuke knife looks a bit like a larger cousin to another Japanese knife called the Bunka. The Bunka, like the Santoku, is a general-purpose kitchen knife, but it features a kengata (angled) tip just like the Kiritsuke. In fact, the Bunka is essentially a Santoku with a K-tip: it has a similar blade length (usually ~5-7 inches), a tall blade profile, and is double-beveled – but with the tip area “clipped” to form a pointed angle.

The word Bunka means “culture” (文化) in Japanese, and the knife was likely developed in the mid-20th century as a versatile home cooking knife as Japan’s diet began incorporating more Western ingredients (similar to how the Santoku came about).

Size & Profile:

As mentioned, Bunka knives are smaller – typically around 165mm (6.5”) blade length, give or take, comparable to Santoku sizes. They have a wide blade like Santokus (often tall enough to comfortably rest your fingers against the side while chopping). The Kiritsuke is significantly longer and usually narrower in blade height. Because of the size difference, a Bunka feels more agile and is better for tight tasks or small hands, while a Kiritsuke can tackle larger ingredients in one stroke due to its length.

Edge & Bevel:

Almost all Bunka knives are double-beveled, making them easy to use by anyone (righty or lefty) and simpler to maintain. In contrast, a traditional Kiritsuke is single-beveled and aimed at right-handed users (unless a special left-handed version is made). This means the Bunka carries no learning curve – you use it like any chef’s knife – whereas the Kiritsuke might require practice for straight cuts if you’re new to single bevels.

Blade Shape Details:

Both have the reverse tanto tip (K-tip). On a Bunka, because the blade is shorter, the angled tip is a smaller portion of the blade but still very handy for precision work. On a Kiritsuke, the K-tip is more pronounced simply due to the blade’s length. The Bunka’s blade edge is usually a bit more curved towards the tip than a Kiritsuke’s dead-flat edge, which can allow a slight rocking motion if needed (though they’re still pretty flat overall). The Kiritsuke’s long straight edge really enforces a push/pull technique.

Intended Usage:

Bunka knives were designed as multi-purpose home kitchen knives – think of them as an alternative to the Santoku. They excel at chopping vegetables, slicing boneless meats, and general prep. The pointed tip also gives Bunkas an edge (pun intended) for detailed tasks like trimming sinew from meat or cutting patterns into veggies, somewhat similar to how one might use a petty knife or paring knife. A Kiritsuke can do these fine tasks too (arguably even better, due to its sharper single bevel tip), but the Kiritsuke’s longer blade makes it a bit unwieldy for small jobs that a Bunka would handle effortlessly. On the flip side, if you tried to fillet a larger fish or slice a whole side of salmon, a Bunka might be too short – that’s where the Kiritsuke’s length is advantageous.

Skill Level & Audience:

The Bunka is suitable for all skill levels, from beginners to pros. It’s forgiving and straightforward. The Kiritsuke is best for experienced cooks or those willing to practice – especially if we’re talking about the single bevel version, which “requires skill to use effectively” and is traditionally reserved for experts. A home cook who has only used Western knives might pick up a Bunka and immediately feel comfortable (aside from adjusting to the super sharpness). That same person might find a Kiritsuke intriguing but potentially intimidating at first.

Versatility:

In terms of the range of tasks, a Bunka can almost replace a Santoku or Gyuto in daily use – it’s that versatile. A Kiritsuke, while very flexible within a Japanese cooking context, might not be what you reach for to smash garlic cloves or halve a watermelon (not that a Bunka is great for watermelon either, but you get the idea). Many people consider the Bunka a great all-around knife for home cooking, while the Kiritsuke is seen as a more specialized tool or a centerpiece knife.

To summarize: If you want the cool K-tip design but primarily need a compact, do-everything knife for home cooking, the Bunka is your friend. It offers a blend of Santoku practicality with a touch of Kiritsuke’s precision tip, all in a very user-friendly package. If you are drawn to the Kiritsuke’s traditional aura, larger size, and are focusing on tasks like sashimi or larger-scale prep, then Kiritsuke stands apart. Some cutlery enthusiasts even own both – a Bunka for quick weekday meals and a Kiritsuke for those special occasions of sushi-making or whole fish preparation.

GENSAKU: “From a craftsman’s perspective, a Bunka is like a modern solution – it gives you versatility with a clever tip – whereas a Kiritsuke is a classic challenge – it gives you high performance if you rise to meet it. One bridges traditional and modern cooking, the other was once reserved for executive chefs only. Their profiles look similar, but their spirit and scale are different.”

In essence, you might choose a Bunka if you’re looking for a practical everyday knife with a bit of flair, and choose a Kiritsuke if you’re looking for a precision instrument steeped in tradition. Both are excellent knives; it’s more about which fits your usage and comfort.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Kiritsuke Knife

By now, we’ve touched on many points regarding what the Kiritsuke can and cannot do. Let’s clearly list out the pros and cons of using a Kiritsuke knife in general, especially from the perspective of a home cook:

✅ Advantages of a Kiritsuke:

- Multi-Tasking Convenience (within Japanese Cuisine): The Kiritsuke can perform tasks that would normally require two or three different knives. If you frequently prepare fish and Japanese dishes, a Kiritsuke saves you from switching between a Deba (for bones), a Yanagiba (for sashimi), and maybe even an Usuba (for veggies). For example, when making a sashimi platter, you can fillet the fish and slice it with one knife. This can streamline your workflow and reduce cleanup.

- Precise, Clean Cuts: Thanks to its extremely sharp edge (often single-bevel) and straight blade, the Kiritsuke excels at making very clean cuts without crushing. This is great for achieving beautiful presentation – sliced fish has smooth, glossy surfaces; vegetables cut with a Kiritsuke have neat edges that show off patterns or textures. If you’re doing any decorative work, the Kiritsuke’s precision is a big plus. Many users report that a Kiritsuke “cuts like a laser,” especially through soft or delicate foods, due to the acute edge angle.

- Unique Angled Tip for Detail Work: The pointed tip acts almost like a small utility knife for detail tasks. You can make incisions, cut out eyes or blemishes from vegetables, bone a fish around the collar, or score meat/fish with fine control. It’s like having a built-in paring knife at the end of a chef’s knife. This can be useful in unexpected ways – for instance, if you need to open up a shrimp to devein it or carve a design into the skin of a squid, that tip is incredibly handy.

- Superior Sashimi Slicing (for its size): While a Kiritsuke may not be as long as some Yanagiba blades, it is still a very capable slicer for sashimi and crudo. Especially for smaller fish fillets or block of fish, a Kiritsuke can slice through in one smooth pull cut, yielding slices almost as clean as a dedicated sashimi knife. The single-bevel edge helps here by reducing friction (food is less likely to stick to the blade), resulting in pristine slices of fish or meats. If you occasionally serve sashimi or carpaccio, the Kiritsuke lets you do so without needing a separate yanagi.

- Versatility with Fish and Seafood: If you love cooking seafood, the Kiritsuke is advantageous. You can use it to butterfly shrimp, fillet fish, slice fish, skin fish, and even do fine chopping (like making fish tartare or negi-toro). It’s truly at home in tasks related to fish. Its blade can handle fish from small sardines up to medium-sized salmon or tuna loins (though very large fish would need longer blades). For things like preparing sushi toppings or cutting thin sheets of konbu (kelp), the Kiritsuke’s sharpness and control are a boon.

- Traditional Aesthetic and Craftsmanship: Beyond functionality, owning a Kiritsuke is appealing to many for its craftsmanship and cultural value. These knives are often beautifully made – you might find ones with gorgeous hamon lines (temper lines) on the blade, elegant octagonal wood handles, and other artisanal touches. There’s a certain pride and joy in using a knife that’s steeped in tradition. It can make cooking feel more artful. Practically speaking for SEO, this might not affect performance, but it affects user engagement – you want to use a Kiritsuke because it’s such a pleasure, which might encourage you to cook more or try new techniques.

- Conversation Piece: Let’s face it, a Kiritsuke is a cool knife to show off. If you have dinner guests or friends who are knife enthusiasts, pulling out a Kiritsuke is sure to spark interest. It’s not a common item in most home kitchens, so it demonstrates a level of culinary adventurousness. While this is not a cooking advantage per se, it adds to the enjoyment factor for the user, which is worth noting.

❌ Disadvantages of a Kiritsuke:

- Steep Learning Curve: Using a Kiritsuke, especially a single-bevel one, requires practice and proper technique. If you’re not used to single-bevel knives, you might find your cuts veering off to one side (single-bevel knives tend to pull toward the flat side). You also have to adjust to not using a rocking motion. Beginners might initially get frustrated when a simple task like chopping a carrot results in slices that aren’t perfectly even because the blade angle was off. Sharpening a single-bevel Kiritsuke is another challenge – you have to maintain the correct bevel angle and polish the flat side, which is different from sharpening Western knives.

- Limited Rocking/Chopping Ability: The Kiritsuke’s long flat profile means it’s not great for western-style chopping techniques like rocking the knife over herbs or swiftly dicing through something in a seesaw motion. If you try to rock it, you’ll find the tip digs in and the middle doesn’t make contact properly. This can slow down tasks like mincing garlic or herbs finely. By comparison, a Santoku or Gyuto allows you to either rock or at least tap-chop quickly, so they can be faster for certain tasks. The Kiritsuke basically forces you into a specific cutting style (push and pull slicing), which while effective for many things, is not universal.

- Not Meant for Hard Bones or Heavy Butchery: While it has some heft, a Kiritsuke is not a cleaver or heavy butcher’s knife. Its tip could chip if twisted in a bone, and its edge (especially if very hard steel) can chip on really hard materials. If you tried to cut through beef bones or even very hard squash with a Kiritsuke, you risk damaging the edge. It’s also not the knife you’d want to use to hack through a crab shell or frozen food. So there is a limitation on what it can chop; you might still need a heavier knife for those kinds of jobs.

- “Neither Here Nor There” Perception: Some cooks critique the Kiritsuke as being jack of all trades, master of none. For example, professional sushi chefs who already have a Yanagiba for fish slicing and a Usuba for vegetables might see no need for a Kiritsuke – why use a compromise when you have the best tool for each job? In a home context, if you already own a good chef’s knife and maybe a fillet knife, a Kiritsuke could feel redundant. It’s a fair criticism: if one isn’t frequently exploring its dual-purpose niche, it might sit idle. For someone who doesn’t often do both fish and veg prep in the same session, a Kiritsuke could end up being an over-specialized toy.

- Maintenance and Care: Traditional Kiritsuke knives are often made of high-carbon steel (not stainless) to achieve that razor sharpness. This means they can rust or discolor easily if not cared for. You can’t leave it wet or dirty – it must be washed and dried promptly after use. For users accustomed to dishwasher-safe stainless steel steak knives (which can be rinsed and forgotten), this is a significant change in habit. Additionally, the sharp edge is delicate; you shouldn’t scrape your cutting board with it or cut into very hard surfaces. In short, a Kiritsuke demands more careful maintenance (regular sharpening, oiling if carbon steel, careful storage to protect the edge) than the average kitchen knife. This can be seen as a con for the busy or carefree cook.

- Availability and Cost: Good Kiritsuke knives are not as mass-produced as chef’s knives or Santokus. They tend to come from specialized knife makers. As a result, a quality Kiritsuke can be quite expensive. Also, there are fewer models on the market, so you might not find one in your local store easily. You often have to order from specialty retailers. If you’re on a tight budget or want to try holding one before buying, this scarcity can be a disadvantage. Meanwhile, Santokus and Gyutos exist at every price point and are easy to find.

- Left-Handed Users Issues: A minor but worth note: if you are left-handed, a traditional Kiritsuke (single bevel) in its standard form won’t work for you (the bevel would be on the wrong side). Left-handed single bevel knives exist, but they are even more niche and often custom-order (and typically pricier). So lefties basically are pushed to either avoid the Kiritsuke or to get a double-edged version. This is a con only for a subset of users, but an important one for inclusivity.

In conclusion on pros/cons: The Kiritsuke’s strengths lie in its versatility for Japanese-style preparations and the precision and beauty of its cuts, while its weaknesses lie in its specialization and demand for skill/maintenance. For the right user, the pros will far outweigh the cons – using the Kiritsuke will feel empowering and enjoyable. For the wrong user, the cons will make it sit in a drawer.

YUKIKO: “At first, I found my Kiritsuke a bit scary – it was so sharp and I actually gave myself a tiny cut because I wasn’t used to the single bevel’s pull. But I practiced slicing cucumbers and fish with it, and now I appreciate how cleanly it cuts. It’s not my everyday knife, but when I use it, I slow down and get zen. The results are worth it.”

GENSAKU: “A Kiritsuke isn’t for hacking pumpkins or splitting chickens – treat it like a precision instrument. If you do that, it will reward you with perfect cuts. If you misuse it, well…don’t say I didn’t warn you when you roll your edge or chip that beautiful tip!”

He says this sternly, emphasizing that respect and proper technique are part of the deal in owning such a knife.

Now that we have a balanced view of its merits and drawbacks, let’s get into the practical side: how do you actually use a Kiritsuke knife effectively? What techniques should you know, and what tips can help you get the most out of it?

How to Use a Kiritsuke Knife (Techniques & Tips)

Using a Kiritsuke knife can be a gratifying experience once you get the hang of it. Here we’ll cover the essential techniques and some tips for common tasks, so you can make the most of this blade while staying safe and efficient.

Mastering the Cutting Techniques

1. Embrace the Push Cut and Pull Cut (No Rocking!):

The Kiritsuke’s straight edge is designed for slicing forward or backward, not for rocking. To cut effectively, use a push cut (glide the knife forward as you press down) or a pull cut (draw the knife toward you while slicing). For example, when slicing a vegetable or boneless meat, start with the tip or mid-blade on the cutting surface, then push forward in one smooth motion so the heel of the blade slides through and finishes the cut. The weight of the knife and sharpness will do the work – you don’t need to saw. Likewise, for a pull cut (commonly used in slicing fish for sashimi), you’d start with the heel and pull the blade towards you in a single stroke, letting the tip exit the cut last, yielding a clean slice.

YUKIKO: “I noticed right away that rocking the Kiritsuke felt awkward. Gensaku taught me to do a deliberate push cut. I practice by slicing paper-thin cucumber rounds, pushing the blade forward each time. Now it’s second nature and I get nice even slices without the ‘see-saw’ motion I used to do.”

If you have muscle memory from Western knives, consciously slow down and make each cut a distinct forward or backward motion. It helps to keep the blade angle consistent and let the length of the blade travel through the food. Over time, this will feel very natural and you’ll gain speed without resorting to rocking.

2. Positioning and Grip:

Use a pinch grip (thumb and index finger gripping the blade just in front of the handle, other fingers around the handle) for maximum control. The Kiritsuke is long, so choking up on the blade gives you stability and balance. When push-cutting vegetables, try to have the flat heel of the blade contact the board at the end of each stroke, ensuring you cut all the way through. Because the blade is straight, you might find it beneficial to slightly lift the handle at the end of a cut to let the tip slice through completely (to avoid any uncut fibers at the bottom of what you’re cutting).

For safety, always be aware of that sharp tip. It’s easy to accidentally poke things with it if you’re not used to it. When you pick up or set down the knife, mind the tip clearance.

3. Guiding the Blade:

With single-bevel Kiritsuke knives, remember that the blade will naturally veer towards the flat side. So if you’re right-handed (bevel on right side), the knife might pull a bit to the left as you cut. Compensate by adjusting your angle or the pressure slightly. One trick is to focus on keeping the blade vertical as you cut, not letting it tilt. Let the sharpness do the work – you shouldn’t need to force it in any direction. With practice, you’ll cut straight down effortlessly.

Specific Use Cases and Tips

Filleting a Fish: One of the hallmark uses of Kiritsuke is to break down whole fish. Here’s how you might do it:

- Use the heel for larger cuts: Start by cutting off the head of the fish. Position the fish, and using the part of the blade near the handle (where it’s thickest), press down to cut through the bone behind the gills. You might not sever in one go if it’s a thick bone; in that case, use a gentle see-saw with the back of the blade or make two cuts from either side meeting in the middle. The Kiritsuke’s heft can generally handle heads of small to medium fish (e.g., sea bream, trout).

- Slide along the backbone: Insert the tip near the head end and slide the blade along the backbone towards the tail in one smooth motion to remove the fillet. Because the Kiritsuke is long and sharp, you can often do this in a single stroke. YANAGAWA: “I angle the blade slightly down towards the bones and pull it towards me – the fillet lifts off like opening a book.” The flatness of the blade helps it stay right against the bones.

- Use the tip for rib bones: Once you have a fillet, use the tip of the Kiritsuke to cut away the rib cage bones. The angled tip acts almost like a deboning knife here. Gently insert just the tip under the rib bones and slice them away from the flesh with shallow cuts. The precision is excellent – you’ll leave very little meat on the ribs.

- Skinning (if needed): If you want to remove the skin from the fillet, the Kiritsuke can do that too. Grip the tail end of the fillet, slide the knife between the flesh and skin at a shallow angle, and then pull the skin while sliding the blade in the opposite direction. Essentially, you keep the knife somewhat stationary (with a slight sawing if needed) and pull the skin toward you – the fillet comes off cleanly. The long flat blade helps make consistent contact, so you don’t accidentally poke through the skin. It’s very similar to using a Yanagiba for skinning fish.

Tip: For very large or very hard-boned fish, don’t force the Kiritsuke. Use a deba or heavier knife for the initial butchery, then use the Kiritsuke for precision slicing.

YANAGAWA (Sushi Chef): “I wouldn’t take my Kiritsuke to a thick grouper bone – I’ll break that with a deba first. But after that, my Kiritsuke handles the fine cuts.”

Know the limits of the knife and you’ll avoid damage.

Slicing Sashimi or Boneless Proteins:

This is where the Kiritsuke truly shines. Ensure your fillet or meat is free of bones. Lay it on the cutting board. Align your Kiritsuke at the angle you want to slice (typically a slight diagonal bias cut for sashimi). Then perform a single, smooth pull-cut: start at the heel, draw the blade towards you through the fish, and let the tip exit at the end of the slice. Ideally, you do not saw back and forth – one clean motion yields the best surface.

Because the Kiritsuke isn’t as long as some sashimi knives, if the piece of fish is very large, you might have to use a slight forward-back motion. But try to minimize it to avoid a serrated-looking edge. Wiping the blade between cuts can also maintain clean slices (since any residue can create friction).

For slicing cooked meat or terrines thinly, the same method applies. You may also use a slight draw-and-push combo: draw halfway, then push forward to finish, effectively using the full length of the blade on a larger cut. The goal is always a clean slice in as few strokes as possible.

Chopping and Julienning Vegetables:

When cutting vegetables (onions, carrots, daikon, etc.) with a Kiritsuke, use a straight down chop or push cut. For an onion, for instance, you can still do the typical horizontal and vertical pre-cuts for dicing, then bring the Kiritsuke straight down to dice. The flat blade might cause a suction effect on wet foods (like potato or onion can stick to the side). Some Kiritsuke knives have a Damascus or textured finish which helps release food; if not, you can just swipe off the pieces with your finger (carefully along the spine side).

For julienning, say you want thin matchsticks of daikon or carrot: first cut the vegetable into uniform slices (Kiritsuke will make clean slices with ease). Then stack a few slices and use a push cut to make fine strips. The weight of the blade and its straight edge help keep the cuts straight. You might find it easier than using a shorter knife because the Kiritsuke’s length stabilizes the cutting line.

If you’re doing a lot of veggie chopping and miss the rocking motion, one workaround is to use a “small forward chop”: lift the knife just a bit and push forward as you come down repeatedly. It’s not a true rock, but a rhythmic push chopping. This works well for things like chopping cabbage or herbs roughly. It keeps that tip from catching since you’re always moving forward.

Decorative Cuts (Kazarigiri):

Kiritsuke is fantastic for decoration. For example, the classic Japanese carrot flower: you cut a series of V-shaped notches around a peeled carrot, then slice the carrot into rounds to get flower shapes. The Kiritsuke’s tip can dig out those notches cleanly. You’d hold the carrot and carefully push the tip in at an angle, carve out a wedge, and repeat. The precision of the tip means you get nice sharp petals on your carrot flower – something hard to do with a curved blade.

Another decorative cut is making a lattice on a mushroom or eggplant. Use the tip to score lines one way, then perpendicular lines to create little squares on the surface. The key is to barely cut through – and the Kiritsuke’s tip gives great control over depth.

For fine garnish slicing, like super thin cucumber ribbons or radish slices, the Kiritsuke’s flat blade helps keep consistent contact. You can also do the katsuramuki (rotary peeling of a daikon into a paper-thin sheet) with a Kiritsuke, though traditionally done with an Usuba. It’s challenging, but the single bevel Kiritsuke actually is capable of it in skilled hands, since it has a similar flat profile and sharp edge. This is an advanced technique where you continuously peel the daikon by moving the knife sideways while rotating the radish. If you’ve mastered it with an Usuba, you can likely do it with a Kiritsuke.

Cutting Meat and Poultry:

You generally wouldn’t use Kiritsuke to chop bones (like through a chicken leg bone – better to joint the chicken properly or use a heavier cleaver). But for slicing meat, it’s great. If you have a roast or a steak, you can certainly slice it with a Kiritsuke into beautiful even slices. The long blade helps you carve in one go. If you need thin slices of chicken breast or pork for stir-fry (for example), partially freeze the meat and then use the Kiritsuke to slice thinly against the grain. The single bevel edge will reduce any dragging, so you can get paper-thin slices of protein for dishes like sukiyaki or cheesesteak, etc. Keep in mind raw meat is a bit stickier than fish, so you might have to use your other hand to gently hold the slice as you cut to prevent it from sticking and lifting with the knife.

For butterflying meats (like opening up a chicken breast or filleting a pork loin for roulade), the Kiritsuke’s tip and sharp edge make it easy to control the depth of your cut as you cut horizontally. It’s similar to filleting a fish.

Using the Kiritsuke’s Flat Side:

If your Kiritsuke is single-beveled, the back side (flat side) can be used for certain tasks like scraping or scooping. For instance, after mincing something, you can flip the knife over and use the spine or the flat side to scrape food off the board without dulling the edge. Some chefs also use the back to scale fish (scraping the scales off) so as not to risk chipping the edge on fish scales – though many Kiritsuke users might prefer a dedicated scaler or the back of a deba for that. Still, it’s an option if you’re trying to minimize tools.

Keeping it Sharp and Safe

Sharpening: To effectively use a Kiritsuke, keep it very sharp. A dull Kiritsuke defeats its purpose, as it will crush and wedge rather than glide. Sharpening a single bevel involves working the bevel side on a whetstone at the original angle (often around 15 degrees or less) until you raise a burr on the flat side, then polishing the flat side by laying it nearly flat on the stone to remove the burr. If you’re not comfortable with that, consider having it professionally sharpened, or practice on less expensive knives first. The good news is, high-carbon Kiritsuke knives take extremely sharp edges, and with stones like 1000 grit for basic sharpening and 3000+ for polishing, you can get a screaming sharp edge that will make usage a joy.

GENSAKU: “A sharp Kiritsuke should sail through paper under its own weight. I sharpen mine before any major use – it’s a ritual, and it means I never struggle when cutting.”

If you have a double-bevel Kiritsuke, sharpen it like any chef’s knife (but maintain the angle – many Japanese double-bevels like Shun’s Kiritsuke have about a 15-degree per side angle).

Honing:

For double bevel versions, you can use a honing rod (ceramic recommended, not coarse steel) occasionally to tune up the edge. For single bevel, usually you’d touch it up on a fine stone rather than using a rod.

Cutting Surface:

Always use a soft cutting board (wood or plastic) with your Kiritsuke. Hard surfaces like ceramic, glass, or granite will dull or chip the fine edge very quickly. A wooden board complements a Kiritsuke well and preserves its edge.

Storage:

Store the Kiritsuke properly – ideally in a knife sheath (saya) or a slot in a knife block, or on a magnetic strip where it won’t knock into other tools. The tip is vulnerable if the knife is jostled in a drawer, so don’t just toss it in with other utensils. A saya (wooden sheath) is a traditional way to protect the blade (many Kiritsuke knives come with one, or you can buy one separately sized to your blade).

Cleaning:

As noted, if it’s not stainless, dry it immediately after use. Even during use, if you cut something acidic (like a lemon or tomato), wipe the blade to prevent patina or corrosion. Some patina (blue/grey discoloration) is natural on carbon steel and not harmful – many chefs let a light patina build as it can actually protect from rust. Just avoid red rust (active rust) by keeping it clean and dry. For stainless versions, maintenance is easier but still treat them well to keep the polish and edge.

By following these usage tips, you’ll find that the Kiritsuke can become an extension of your hand for the tasks it’s meant for. It may feel different from what you’re used to, but that difference is what brings its performance and results to another level. As you become comfortable, you might discover that some tasks you used to dislike (like finely slicing fish or making garnishes) become almost meditative with the Kiritsuke.

YANAGAWA: “When I plate sashimi now, I see the difference. Using my Kiritsuke, each slice of fish has a clean shine and uniform thickness. Even the way the knife exits the cut – that clipped tip doesn’t snag, it just slides out, leaving the slice neatly separated. It’s a small detail, but for me, those details accumulate into the art of Japanese cooking.”

With practice and care, you’ll be leveraging the Kiritsuke knife’s full potential and appreciating why it holds such a storied place in the realm of Japanese cutlery.

Modern Variations: Double-Bevel Kiritsuke and Stainless Steel Options

The traditional Kiritsuke is a single-bevel carbon steel knife that requires expertise, but recognizing the needs of modern cooks, many manufacturers have introduced variations to make the Kiritsuke more accessible and user-friendly. Two main trends are double-bevel Kiritsuke knives and the use of stainless steel alloys for easier care. Let’s explore these:

Double-Bevel Kiritsuke (Kiritsuke Gyuto)

As discussed earlier, a double-bevel Kiritsuke is essentially a Kiritsuke-shaped chef’s knife. Sometimes called a Kiritsuke Gyuto or simply sold under the name “Kiritsuke,” these knives have symmetrical edges, meaning both sides of the blade are sharpened, typically at around 15 degrees per side in Japanese style.

Why double bevel? In today’s world, not every chef (and certainly not every home cook) is trained on single-bevel knives. Also, there are many left-handed cooks out there who would love to use a Kiritsuke without ordering a special lefty knife. Double-bevel Kiritsuke knives address these issues:

- They are much easier for newcomers. You can pick it up and use it like any normal knife. There’s no learning curve of steering or special sharpening techniques – you can even sharpen many of them with standard sharpening rods or pull-through sharpeners (though whetstone is always better).

- They are ambidextrous. Righties and lefties can use the same knife with equal ease. The edge is centered, so it cuts straight down without bias.

- They tend to have a slightly more robust edge. While still very sharp, a double bevel edge (especially if a bit of a micro-bevel is added on each side) can be a tad more durable than an ultra-refined single bevel edge. That means fewer small chips if you happen to cut something hard or knock the edge.

However, these double-bevel Kiritsukes retain the overall shape – the flat profile and angled tip – so you still get a lot of the Kiritsuke experience. Many popular brands offer them. For instance, Shun (a well-known Japanese knife brand) has a Shun Premier Kiritsuke 8” which is double-bevel and marketed as an all-purpose chef’s knife with a Kiritsuke shape. It’s intended to give Western cooks the feel of a Kiritsuke with none of the drawbacks of single-bevel use.

Performance differences: A double-bevel Kiritsuke will not quite match the laser-like feel of a true single-bevel, especially for sashimi slicing. The edge geometry is different, so the cut might be slightly less glass-smooth (though still extremely good). Also, because there’s usually a bit of curvature (however slight) to ensure the knife can make board contact evenly, the double-bevel versions might rock a little more easily. Essentially, they sacrifice a tiny bit of the traditional finesse for a lot of added convenience.

According to one source, “a double bevel Kiritsuke usually refers to a variation of the Gyuto knife with a Kiritsuke-style edge, often labeled as a Kiritsuke Gyuto or K-tip Gyuto”. This underlines that these knives are really hybrids – Gyuto in function, Kiritsuke in form.

Use cases: If you’re an enthusiastic home cook who wants a Kiritsuke primarily because of its shape and versatility, getting a double-bevel Kiritsuke is a fantastic idea. You won’t have to overhaul your technique or worry about maintenance as much. You can chop herbs or cut onions with it more comfortably. And if you’re left-handed, it’s basically your only practical option to enjoy a Kiritsuke without custom orders. Many professional Western chefs who like the Kiritsuke profile in their kitchens also prefer double bevel because it integrates into their existing toolkit without special handling.

GENSAKU’s take: “When I first saw double-edged Kiritsuke knives coming out, I was a bit skeptical – was it still a Kiritsuke? But I tried one (I think it was a VG-10 steel one), and I admit, it was smooth. I didn’t have to think about angles as much, I could just use it like a normal knife. For a busy restaurant where many hands might use the same knife, a double-bevel Kiritsuke makes sense. Less training needed, fewer accidents with sharpening. It’s a modern solution, and I’m okay with it – as long as people remember it’s not the ‘traditional’ Kiritsuke of old, but something new inspired by it.”

He highlights a key point: these knives are an evolution, keeping the spirit of Kiritsuke but adapting to current needs.

One thing to note: double-bevel Kiritsuke knives are often marketed under general chef knife categories, so if searching, you might find them listed with Gyutos or as “K-tip chef knife.” They might also be more available globally since they cater to a wider audience.

Stainless Steel Kiritsuke Knives (Ginsan and Others)

Traditional Japanese knives were made of carbon steel, which, while great for sharpness, require careful maintenance to prevent rust. To modernize things, many Kiritsuke knives now come in stainless steel versions or stainless-clad versions. One notable steel used is Ginsan (Silver #3), a Japanese stainless steel prized for its carbon-steel-like performance with added chromium for rust resistance.

What is Ginsan (Silver #3)? It’s a high-quality stainless steel created by Hitachi Metals. Ginsan was designed to sharpen and cut like a carbon steel but with none of the maintenance hassles. It has around 13-14% chromium (which makes it stainless) and a high carbon content (around 1%). The purity of the alloy means it forms a very fine grain structure, allowing for a razor edge similar to traditional steels. In practical terms, a Kiritsuke made from Ginsan steel can get almost as sharp and hold its edge almost as well as one made from, say, Shirogami (White #2 carbon steel). The big benefit: it’s much less prone to rusting, so you don’t have to panic if you see a droplet of water on the blade for a minute or two. You still should dry it off, but it won’t instantly discolor. Ginsan steel knives also tend to be easier to sharpen than some other stainless steels, because the alloy is made to mimic carbon steel’s sharpening feel.

Other popular stainless or semi-stainless steels for Kiritsuke knives include VG-10, a very common Japanese stainless that’s hard and wear-resistant, and AUS-8/AUS-10 in more budget-friendly knives, or high-end powder metallurgy steels like SG2/R2 which offer superb edge retention. There are also stainless-clad carbon options – knives where a core of carbon steel (for cutting edge) is laminated with outer layers of stainless steel. These give you the edge quality of carbon but the exposed sides are stainless, reducing maintenance.

Benefits of Stainless Kiritsuke:

- Low Maintenance: You don’t have to worry about wiping the knife every minute or oiling it for storage. This is great for home cooks who might not be used to babying their knives. It also suits professional kitchens that are fast-paced – a chef can focus on cooking rather than on whether their knife is dry.

- No Reactive Taste: Carbon steel can sometimes react with acidic foods (like onions, citrus) and impart a slight metallic taste or cause foods to discolor. Stainless avoids that, which is helpful if you’re cutting lots of apples, potatoes, etc., and don’t want them turning brown from iron reacting.

- Appearance: Stainless knives generally stay shiny if cared for, whereas carbon steel develops a patina (gray/blue hues). Some people love patina (it shows history and character); others prefer the mirror-polish look. If you want your Kiritsuke to remain bright and spotless, go for stainless.

- Stainless Cladding: If you see a knife described as, for example, “Blue #2 core, stainless cladding,” it means the edge is a traditional steel but the outside is stainless. This is a nice compromise: you still have to wipe the edge, but the majority of the blade won’t rust. Many high-end knives use this construction for practical reasons. For Kiritsuke, you might find some that say “stainless clad carbon Kiritsuke.”

One example from the original Japanese content: they mention 銀三鋼 (Ginsan-ko) models, noting that Ginsan is a stainless steel that still offers near-carbon sharpness, and is relatively easy to maintain. They suggest that “if you long for carbon steel sharpness but hate rust, a Ginsan Kiritsuke is perfect – while a bit pricey, its ease of care will boost your happiness”. In other words, the convenience can be worth the cost.

YUKIKO’s concern: “I’m used to tossing my stainless steel steak knives in the sink without worry. Will a Kiritsuke need special care?”

– We addressed this partly, but to reiterate, if you choose a stainless Kiritsuke, you won’t need to worry as much. You should still avoid the sink toss (really, avoid that for any good knife!), but you can treat a stainless Kiritsuke similarly to how you treat a German steel knife: wash it, dry it, store it. It won’t punish you with rust spots for a brief lapse in cleaning.

GENSAKU: “In the past, I’d never imagine a stainless Kiritsuke. But steels have come a long way. Now I forge some Kiritsuke knives in VG-10 or even SG2 powder steel. They’re razor sharp and much easier for customers to maintain. Just remember, ‘stainless’ doesn’t mean ‘stain-never’ – still wipe your knife, eh!”

He winks. Indeed, while stainless offers a safety net, keeping any knife dry and clean is best practice.

One more modern variation to mention is the Kiritsuke-style slicers that are basically Yanagibas with a K-tip (often called Kiritsuke Yanagiba). Those are still single-bevel but just a Yanagiba variant. They are more for sashimi only (not multi-purpose) so not the focus here.

With double-bevel and stainless options, the Kiritsuke design has evolved into something that any passionate cook can incorporate. You get the visual appeal and functionality of that K-tip blade, but you can choose the version that fits your lifestyle:

- Traditionalists or pros might stick with single-bevel carbon Kiritsuke for ultimate performance and heritage.

- Home cooks and modern chefs might opt for a double-bevel stainless Kiritsuke for practicality and ease.

- Enthusiasts might even have both, using the stainless double-bevel for daily work and the classic one for special tasks.

The bottom line is, there’s a Kiritsuke for everyone now. If cost is an issue, even mid-range brands have introduced more affordable double-bevel Kiritsukes in stainless steel, so you don’t have to break the bank to try one.

Choosing Your Kiritsuke: When shopping, consider these factors:

- Do you want traditional single bevel or easier double bevel?

- Do you prefer carbon steel (for edge feel) or stainless (for ease)?

- What blade length suits you? (If you’re not comfortable with 270mm, there are 210mm or 240mm Kiritsukes out there too.)

- Handle type: Most Kiritsukes have a wa handle (Japanese style wooden handle, often octagonal or D-shape). Some modern ones might have Western handles. Go with what you find comfortable and stylish.

- Budget: Kiritsuke knives can range from under $100 for mass-produced stainless versions to several hundred (or more) for handcrafted ones. Generally, you get what you pay for, but even a reasonably priced one can serve well if it’s properly made.

To wrap up this section, modern innovations have lowered the barrier to entry for using a Kiritsuke. As a home cook, you can enjoy the essence of this knife without dealing with all of the traditional downsides, if you choose the right model. This has helped the Kiritsuke gain popularity beyond just master chefs – you’ll now see it in knife sets or recommended lists for avid home cooks. It’s a great time to get to know this knife, because you can tailor it to your comfort level.

Choosing the Right Kiritsuke Knife for You

If you’ve decided that you want to add a Kiritsuke to your kitchen, the next step is choosing one that fits your needs. With the background we’ve covered, you likely have an idea of the options (traditional vs modern, etc.). Here are some key considerations and tips for selecting a Kiritsuke knife, with a focus on what beginners to intermediate users should think about:

1. Purpose and Use Frequency:

Be honest about what you’ll use the Kiritsuke for. Is it going to be your primary knife for daily cooking? Or a specialty knife you pull out for certain dishes (like sushi nights or when you feel like practicing katsuramuki)?

- If it’s going to be a daily driver in place of a chef’s knife, you probably want a double-bevel Kiritsuke, around 8-9 inches, in a durable steel (perhaps VG-10 or AUS-10), because it will handle varied tasks and won’t require as much fuss.

- If it’s more of a special occasion knife and you want the authentic experience, a single-bevel carbon steel Kiritsuke could be very rewarding, since you won’t be subjecting it to abuse and you can take your time with it when you do use it.

2. Blade Length:

Kiritsuke knives come mainly in the 210mm, 240mm, 270mm, and 300mm range. For a home cook:

- 240mm (about 9.5”) is a sweet spot – long enough to get the benefits, but not overly huge.

- 210mm (about 8.3”) Kiritsukes exist (some double-bevel ones at least). These might be good if you have a smaller workspace or simply prefer shorter knives. They sacrifice some slicing length, but are easier to handle.

- 270mm (10.5”) is great for slicing performance, but you need space and a bit more skill to maneuver it especially on a cluttered counter.

- 300mm (12”) is usually for professional use (sushi chefs doing large fish or big volume slicing). Probably overkill for most home kitchens.

If unsure, 240mm is often recommended for multipurpose use (even the Japanese guide suggested ~270mm as ideal for most people, but that’s in a professional context perhaps – 270mm is wonderful if you’re comfortable with it though).

3. Steel Type:

Decide on carbon vs stainless. This often also correlates with price.

- Carbon Steel Kiritsuke (e.g., White #2, Blue #2): Incredible edge sharpness and honing responsiveness. Demands care to prevent rust. If you’re willing to oil your knife or live with patina, these feel very traditional. They may also be slightly cheaper than stainless in some cases (since stainless alloys can cost more to manufacture).

- Stainless Steel Kiritsuke (e.g., Ginsan, VG-10, AUS-8): Much easier upkeep. Still very sharp (especially Ginsan, SG2, etc.). Possibly a tad more expensive if we talk high-end powder steels. For beginners, stainless might be the safer bet to avoid frustration with rust. Knifewear describes Ginsan as allowing knives to “sharpen and cut like carbon steel but with none of the maintenance” – an attractive proposition for many.

- Stainless Clad / Semi-Stainless: Don’t overlook these. A Blue #2 core with stainless cladding is a great compromise: you get the edge quality of Blue #2 (awesome sharpness, edge retention) but mostly worry-free sides. Just keep the edge dry. Semi-stainless steels like SKD11 or Aogami Super (with some chromium) also reduce maintenance slightly.

4. Handle Type:

Most Kiritsukes will have a wa-handle (wooden handle, often ho wood or magnolia wood with a buffalo horn bolster, or various fancy woods). These are lightweight and forward-balance the knife nicely. Make sure you’re okay with a Japanese handle (which is usually larger in circumference but lighter in feel than a Western handle). Some newer Kiritsuke versions might have Western handles (full tang, riveted like German knives). That can add weight and change balance. It’s largely personal preference. Wa-handles can feel weird if you’ve never used them, but many come to love the control they provide. Also consider aesthetics: do you like dark wood, light wood, any particular color? Some brands offer options.

5. Brand and Maker:

Research brands known for quality. Some famous Japanese makers (especially from Sakai, Seki, etc.) produce excellent Kiritsukes. Examples: Sakai Takayuki, Aritsugu, Yoshihiro, Masamoto (these are more traditional). For modern, Shun (Kai), Miyabi, Global even has a take (Global G-77 is a Kiritsuke shape), Dalstrong, etc. Check reviews. Ensure the knife is well-ground (especially that the flatness and edge are well done – a poorly made Kiritsuke could have a slight belly or uneven tip grind that ruins the function).

6. Budget:

Decide how much you want to invest. If you’re just testing the waters, there are entry-level Kiritsuke knives in the ~$100 range (often double-bevel VG-10 or AUS-8). They may not have the absolute best steel or handcrafted touch, but they work. If you already love Japanese knives, you might aim higher, say $200-300 for a really nice one (maybe hand-forged, with quality steel like Blue #2 or SG2). And of course, there are high-end smiths where a Kiritsuke might cost $500+. That’s collector territory or serious hobbyist.

7. Left-Handed Consideration:

If you’re lefty and want a single bevel Kiritsuke, you’ll need to special order one (many makers can do lefty versions, often at a surcharge). But more practically, opt for a double-bevel. It will save you cost and hassle.

8. Try Before Buy (if possible):

Because of the unique shape and length, it’s not a bad idea to hold a Kiritsuke in person if you can. See how the 240 vs 270 feels, or how the balance is. Not everyone has this luxury, but if there’s a cutlery store or a friend with one, it helps to get a feel.

9. Consider a Saya (Sheath):

If one isn’t included and you plan to store it in a drawer or transport it, get a wooden saya for it. It protects that tip from chipping and also protects you when reaching for it. Some sellers include a saya (especially for single bevel traditional ones).

10. Emotional Factor:

This might sound odd, but also choose a knife that speaks to you. Part of using a Kiritsuke (or any high-end knife) is the joy it brings. If the Damascus pattern or the kurouchi finish or the handle grain makes you happy every time you pick it up, that’s a valid factor. You’ll be more inclined to use and care for a knife that you feel a connection to. So take into account which one you love the look of – so long as the functional aspects line up too.

By weighing these factors, you’ll be able to select a Kiritsuke that becomes a cherished tool in your kitchen and not a regretted purchase. For example, Yukiko might choose a 240mm stainless double-bevel Kiritsuke with a lovely rosewood handle – it fits her busy home cooking routine and she doesn’t have to worry about rust with kids running around, but she still gets that Kiritsuke vibe she admires. Gensaku, being old-school, probably has a 270mm white steel single-bevel Kiritsuke he made himself, which he uses to demonstrate techniques and keep his skills sharp. Yanagawa, as a sushi chef, might have multiple – one traditional for sushi prep in the restaurant, and a double-bevel one for events or lending to apprentices who want to learn the style.

Ultimately, the right Kiritsuke knife for you is one that matches your cooking style, skill level, and maintenance commitment. When you have the right fit, it will indeed feel like a “頼もしい相棒” – a reliable partner – as the Japanese text alluded. Cooking should become a bit more enjoyable, and who knows, maybe your Kiritsuke will inspire you to widen your culinary repertoire, as it often invites you to try more Japanese techniques.

Conclusion

The Kiritsuke knife is a fascinating blend of tradition, versatility, and beauty. We’ve explored its definition, compared it with other knives, examined its pros and cons, learned how to use it, and looked at modern adaptations. By now, you should have a thorough understanding of what makes the Kiritsuke unique and whether it’s the right knife for your kitchen.

To summarize the key points:

- Kiritsuke’s Unique Balance: It’s not as thick and heavy as a Deba, and not as long and specialized as a Yanagiba – instead, it strikes a middle ground that is the source of its appeal. This balanced design is the Kiritsuke’s charm: it can handle a variety of tasks in Japanese cooking that would normally require multiple knives.

- Angled Tip Advantage: The Kiritsuke’s signature angled tip (K-tip) opens up a range of delicate tasks – from trimming around fish bones to carving intricate vegetable designs – making it surprisingly multi-functional. That “kaku” or corner at the tip gives you a tool for precision that many other knives lack. It extends the possibilities of how you can cut and present food, from small bone work to sashimi slicing to decorative cuts, broadening your culinary capabilities.

- Jack of All Trades, or Master of None? It’s true that some view the Kiritsuke as “neither here nor there” – a bit of a hybrid that could be seen as redundant if you already use specialized knives. If you’re someone who has and regularly uses a full set of traditional knives (Deba, Yanagiba, Usuba), a Kiritsuke might indeed sit on the sidelines. However, for many cooks who want more flexibility with one blade, the Kiritsuke can become a dependable companion. It’s all about your needs: those seeking a more flexible, all-in-one approach in the realm of Japanese cuisine will find the Kiritsuke extremely valuable, whereas someone content with multiple dedicated knives might not feel the need.

- Beginner-Friendly Options Exist: The presence of double-bevel and stainless steel Kiritsuke models means that even left-handed users, beginners, or those shy about maintenance can still enjoy this knife. Don’t overlook these options – they make the Kiritsuke accessible without having to dive into sharpening nuances or constant wiping. It’s a nod to the modern cook, and a point not to be missed when considering a Kiritsuke.

At the end of the day, if you have a passion for cooking – especially if you’re drawn to fish and refined knife work – adding a Kiritsuke to your arsenal can be a game-changer. It invites you to improve your knife skills and perhaps venture more into Japanese recipes or presentation styles. As the original article hinted: “If you want to make fish preparation more comfortable, or challenge slightly more beautiful plating, a Kiritsuke is worth considering.”. It can truly elevate your kitchen experience, making once tedious tasks feel elegantly efficient.

YUKIKO: “Ever since I got my Kiritsuke, I actually find myself buying fresh fish more often. I’ve gained confidence in filleting, and I love making a simple sashimi for my family – something I wouldn’t have tried before. It’s broadened what I cook.”

For Yukiko, the Kiritsuke opened new doors in home cooking.

YANAGAWA: “When I hold my Kiritsuke, I stand a little straighter. It reminds me of why I fell in love with Japanese cuisine – the precision, the art. Even after 40 years, a knife like this still inspires me to improve my craft.”

For Yanagawa, it’s a source of inspiration and pride.

GENSAKU: “A good knife should make you want to cook. If the Kiritsuke, with all its history and functionality, makes you excited to prepare a meal, then I’d say it has earned its place in your kitchen.”

Whether you’re looking to enhance your skills, diversify your cooking, or simply enjoy the feel of a finely crafted tool, the Kiritsuke knife has a lot to offer. If you do decide to bring one into your kitchen, take your time with it, practice, and soon it may become the 頼もしい相棒 (reliable partner) that helps you shine in your culinary journey.

Happy cooking, and perhaps happy slicing with your new Kiritsuke! Enjoy the process of finding that perfect blade and integrating a piece of Japanese knife mastery into your own cooking repertoire.

Comments