What is a Tuna Knife (Maguro Bocho)?

A tuna knife, known in Japanese as maguro bocho (鮪包丁) or maguro kiri bocho (鮪切り包丁), is an extremely long, specialized Japanese knife designed for cutting large tuna and other big fish. With blade lengths ranging roughly from 30 cm up to 150 cm (12–60 inches) or even more, plus an extended handle for leverage, this impressive tool can fillet an entire tuna in a single stroke.

In fact, the largest maguro bocho resemble swords in size and appearance – hence they’re often nicknamed “tuna sword” – and sometimes require two people to handle: one person guides the handle, and another supports the tip (often gripping it with a towel for safety). These knives aren’t just eye-catching props; in skilled hands they are indispensable for efficiently butchering giant tuna with minimal waste and maximum precision.

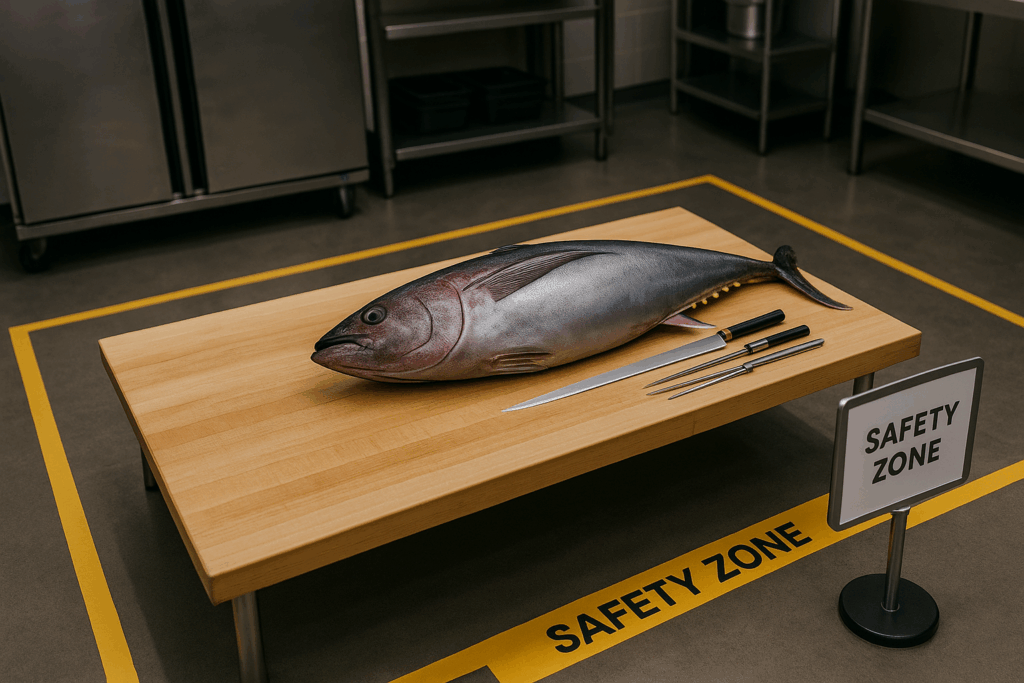

Where are tuna knives used? You’ll typically find maguro bocho in action at wholesale fish markets (most famously at Tokyo’s Tsukiji Market) during tuna auctions and filleting demonstrations. It’s here that skilled fishmongers dramatically break down enormous tuna using these blades, often in front of onlookers. High-end sushi restaurants that purchase whole tuna may also keep a tuna knife on hand, especially if they frequently process large (200 kg+) tuna.

Outside Japan, similar large tuna knives are used in big seafood markets around the world – for example, fish markets in Taiwan also employ long “Taiwan tuna knives” for breaking down locally caught bluefin tuna. However, you won’t see a maguro bocho in a typical home or small restaurant kitchen (unless it’s for display), as its size and purpose are very specialized.

YANAGAWA

YANAGAWAYANAGAWA (Sushi Chef, 60s): “When I first saw the maguro bocho in action at Tsukiji, I was amazed. It looked like a samurai sword slicing through a giant tuna! But once I tried it myself, I understood it’s not just for show – that long blade let me slide through an entire tuna loin in one go, with a clean cut that preserves the flesh. It’s a knife on a completely different scale, and it makes butchering a 200-kilo tuna surprisingly efficient.”

Despite its dramatic sword-like form, the maguro bocho is fundamentally a practical tool for professionals. Its true value lies in enabling a skilled chef or fishmonger to break down huge fish quickly, cleanly, and with minimal waste. By using one continuous drawing cut, a tuna knife can separate big fillets without the back-and-forth sawing that would tear the flesh. The result is pristine cuts of tuna – vital for high-quality sashimi and sushi – and improved yield (less meat left on the bones). In short, the maguro bocho is the ultimate knife for butchering giant tuna efficiently while maintaining presentation quality.

Types of Tuna Knives and Their Uses

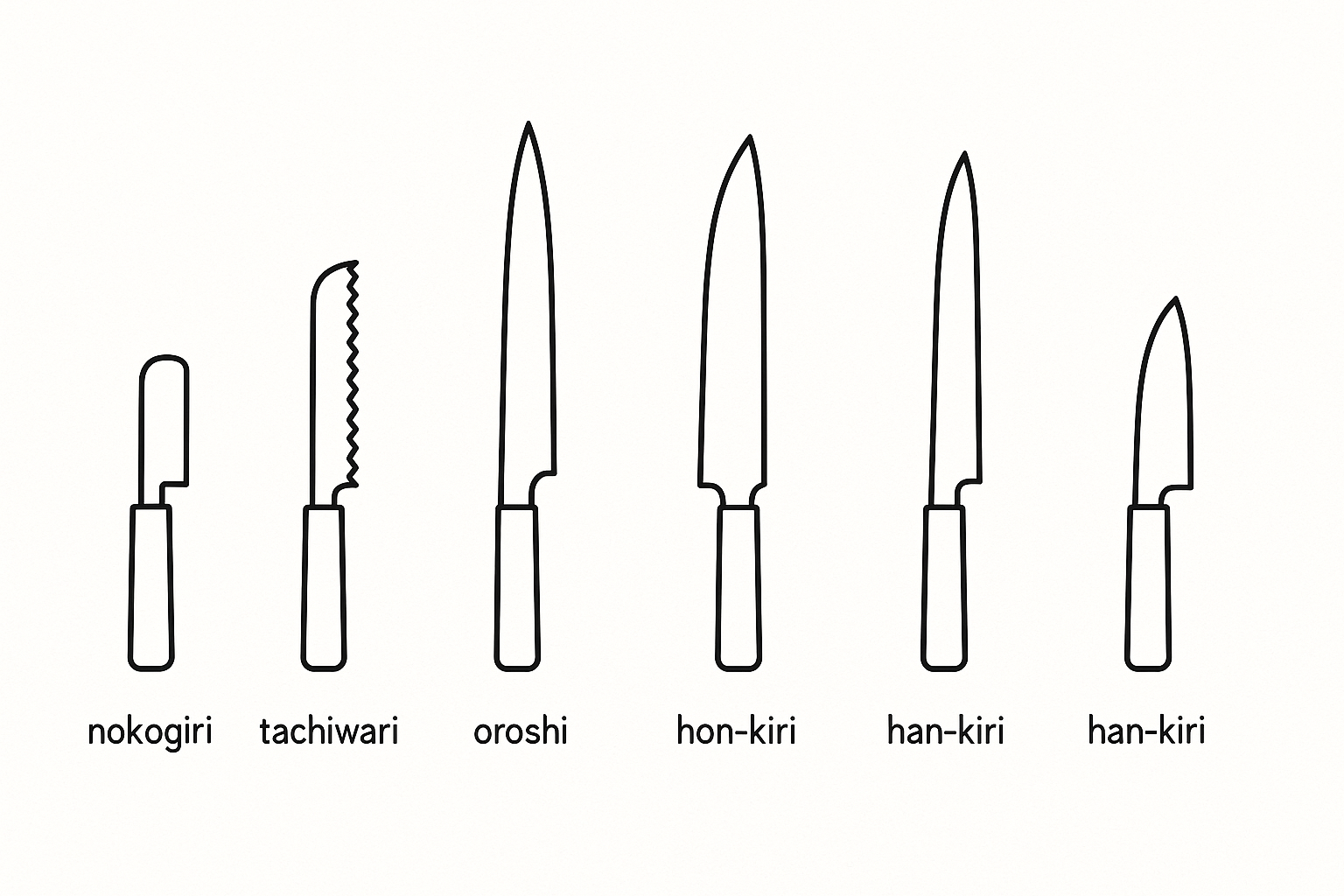

When we talk about “tuna knife,” we generally mean the maguro bocho used to fillet tuna. However, in Japanese tuna processing, there are actually five types of specialized knives, each for a different stage of breaking down a tuna. These range from relatively short, stout blades for initial cuts to the massive sword-like blades for filleting. Here are the main types of maguro bocho and what they’re used for:

| Type of Maguro Bocho | Primary Use |

|---|---|

| Nokogiri bocho (“saw knife”) | Cutting off the tuna’s head and tough fins. This knife often has serrations or a hefty blade to saw through bone and cartilage. |

| Tachiwari bocho (“splitting knife”) | Splitting the tuna from back to belly along the backbone. Used to open the tuna’s body cavity by cutting down through the spine. |

| Oroshi bocho (“filleting knife”) | An extremely long blade (often resembling a katana) used to fillet the tuna and separate flesh from bone. This is the classic “tuna sword” used in fillet shows. Some oroshi bocho exceed 1800 mm (6 feet) in length and may require multiple people to handle. |

| Hon-kiri bocho (“final cut knife”) | Used for portioning the tuna’s loins into smaller, manageable pieces (saku blocks) after the initial filleting. It ensures the large fillet is cut down to serving or storage sizes. |

| Han-kiri bocho (“half-cut knife”) | Used to cut a whole tuna into halves (typically cutting through the center of the fish). This is a very specialized knife, rarely seen outside wholesale markets and not commonly sold to the public. |

Most professional tuna breakdowns will prominently feature the oroshi bocho for the filleting step, and perhaps a tachiwari bocho for splitting, as those are the critical, dramatic cuts. The other types (head cutter, portioning knives) might be used behind the scenes.

It’s worth noting that these category names are based on usage, not strict designs – you might not see the names labeled on knives sold in stores. Often a single maguro bocho can serve multiple functions depending on technique. But understanding the different stages of tuna butchery helps explain why various shapes and sizes of knives exist.

YUKIKO (Japanese Chef, 32s): “Watching a maguro kaitai (tuna filleting show), I noticed they switched knives – a shorter sturdy one to remove the head, then that huge sword-like oroshi hocho to slice out the fillets. It made me realize how specialized these knives are. Each step – head, spine, fillet, portions – has an ideal tool. You wouldn’t try to hack off a tuna head with a long flexible blade, and likewise a short knife wouldn’t make a clean sweep through a big fillet. The right tool for each job makes the work faster and cleaner.”

A Closer Look at the “Tuna Sword”

The oroshi bocho, often just called maguro bocho, is the most iconic tuna knife. It’s typically a single-edged, very long blade with a pointed tip, looking much like a slender sword. Why such extreme length? There are a few critical reasons:

- One-Stroke Cuts: A blade over 1 meter long allows the chef to slice through an entire cross-section of a large tuna in one continuous pull cut. Fewer strokes mean a cleaner cut surface and less damage to the flesh. Instead of sawing back and forth (which can crush the meat and create ragged edges), the chef draws the long blade once to cleanly separate loins or large sections. This preserves the quality of the tuna, yielding beautifully smooth fillets. It also speeds up the process – a seasoned chef can cut a huge tuna loin in seconds with a well-placed draw of a maguro bocho, whereas using shorter knives would be much slower.

- Minimal Waste: Tuna have complex bone structures and strong connective tissues. The maguro bocho’s length and flexibility allow it to follow the curvature of the fish’s bones closely, which minimizes meat left on the carcass. With a long blade, you can run along the spine from nose to tail in one go, neatly peeling the flesh off the bone. This precise approach maximizes yield, which is important given the value of premium tuna.

- Reach and Leverage: The length also provides reach to cut through very large specimens. A giant bluefin tuna can be over 2 meters long and extremely thick; a regular kitchen knife simply can’t span across the body. The maguro bocho’s extended reach means you can cut through the width of the fish or along its length without having to cut from both sides. The long handle gives leverage and control over the big blade. In practice, when a tuna is laid out on a table, a chef can stand above and draw the blade through the fish in a single motion, something impossible with a shorter knife.

The tip of a tuna knife is usually pointed and reminiscent of a katana. This sword-like tip is not just for show – it’s functional. A sharp, narrow tip allows the chef to make precise incisions and navigate around bones and fins inside the tuna with minimal flesh damage.

For example, when detaching the tuna’s head or tail or trimming around the rib cage, the pointed tip can be worked into tight spots to gently separate meat from bone. The slender tip is also crucial for delicately working through the prized otoro (fatty tuna belly) area – it lets you slice away the fillet from the skin and bone without gouging too deeply into the soft fat, ensuring that valuable piece comes off cleanly. In essence, the maguro bocho’s blade combines length for sweeping cuts with a fine tip for detail work, making it a versatile tool for a very large task.

Interestingly, many maguro bocho blades have a bit of flex (springiness) to them, rather than being extremely stiff. This is by design. A slight flex in the long blade is advantageous because it bends along the fish’s body and “gives” if it hits a hard bone, rather than chipping or abruptly stopping.

The flex helps the blade glide along vertebrae and ribs without digging in, so you can keep the cut smooth. It also reduces the chance of tearing the flesh – when encountering resistance from bone or tough sinew, a flexible blade will yield slightly, avoiding a sudden jerk that could rip the meat. Experienced tuna cutters often develop a preference for a certain amount of blade flex that suits their technique.

Some blades are made more rigid for power, others more springy for finesse. High carbon steel blades, for instance, can be tempered to have a bit of spring. The key is that the blade should not be so rigid that it shatters or so floppy that it’s hard to control. A well-made maguro bocho has the right balance of hardness and elasticity: hard enough to hold a razor edge, but springy enough to absorb shocks. This characteristic is one of the secrets to making such a long knife effective.

GENSAKU (Master Bladesmith, 60s): “When forging a maguro bocho, I deliberately temper it so the blade isn’t too stiff. A little bend is good – it means that when the blade hits a backbone, it’ll flex slightly and trace along the bone instead of wedging in. Too hard and brittle, and you’d chip the edge or crack the fish’s bone; too soft, and the knife would whip around. It’s a delicate balance. I tell chefs: the first time you use a proper tuna knife, you’ll feel it – the blade sort of hugs the bone as you slice, coming out with all the meat cleanly. That’s when you know the knife’s doing its job right.”

Material and Construction

Traditional maguro bocho are often made of high-carbon steels (such as Japanese white steel #2 or blue steel) which can take an exceptionally sharp edge. These steels allow a master sharpener to hone the blade to “razor” level sharpness – crucial when slicing through delicate fish flesh cleanly. The downside is carbon steel can rust easily, especially in contact with salty fish and water, so rigorous maintenance (cleaning and drying immediately after use, oiling for storage) is needed. Modern versions of tuna knives are sometimes made from stainless steel or high-tech alloy steels to address this. Stainless blades don’t rust and are easier to maintain, which is beneficial in the messy environment of a fish market or for a traveling sushi demonstration. However, some professionals feel that traditional carbon steel still takes a keener edge. In recent years, knife makers have improved stainless cutlery steels to be both hard and rust-resistant, so a good stainless maguro bocho can perform nearly on par with carbon steel and is much less hassle to care for. Ultimately, the choice comes down to the user’s priorities: ultimate sharpness vs. ease of maintenance. Many pro chefs in Japan still swear by carbon steel for their tuna knives (and simply accept the need to wipe down the blade frequently), whereas others appreciate the convenience of stainless, especially when doing filleting shows or working in humid conditions.

Maguro bocho are single-beveled knives (like most traditional Japanese knives, sharpened on one side), which allows extremely precise cuts and keen edges. The back side of the blade often has a gentle concave grind (urasuki) like a yanagiba, which helps food not stick and makes sharpening easier. In essence, a tuna knife is like an oversized yanagiba sashimi knife in its blade geometry – but much longer and sometimes thicker. The blades are usually fairly thin relative to their length, to slide through fish flesh with low resistance. They often come with a wooden sheath (saya) to protect the edge (and for safer transport, as an unsheathed 5-foot blade is an accident waiting to happen).

The handles on maguro bocho tend to be elongated versions of traditional Japanese knife handles (often made of wood like ho wood, sometimes oval or octagonal in shape).

They are made long enough to provide balance to the long blade and to allow a two-handed grip if needed. Unlike a samurai sword, however, the handle isn’t usually wrapped – it’s a smooth wooden handle similar to other Japanese kitchen knives, just larger. Some maguro knives even have a slight hook or pommel at the butt of the handle to prevent slipping, but most rely on the user’s firm grip and proper technique. Weight-wise, a large tuna knife can be several kilograms, so the handle must be gripped securely and the user often uses their whole body to pull the blade through the fish. This is why proper stance and space are important (more on that below).

Using a Maguro Bocho: Technique and Safety

Using a tuna knife is an art in itself. For those new to it, the first impression is often the sheer size and weight of the knife – it can feel unwieldy. But with the right technique, it allows a skilled chef to break down a tuna with efficiency and grace. Here are key points on operation and best practices:

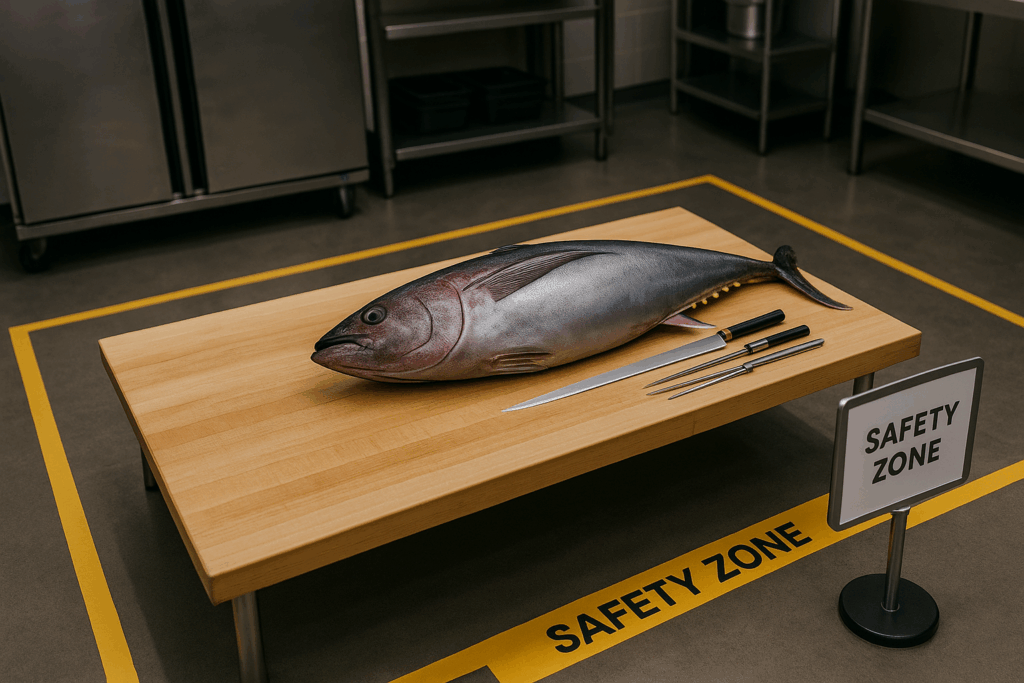

Workspace:

Because of its length, you need a large, clear workspace to operate a maguro bocho safely. Professional tuna handlers set up a long cutting table or board, and ensure no obstructions (or people) are in the path of the blade. Remember, swinging or drawing a blade that’s over a meter long requires room. It’s common sense but worth emphasizing: never attempt to use a tuna sword in a cramped kitchen!

Grip and Stance:

Typically, the chef stands sideways to the fish, holds the maguro bocho with the dominant hand on the handle and the other hand either guiding the blade spine or also on the handle if there’s room. For very large knives, a second person may assist by holding the far end of the blade lightly (with a thick towel wrapped around the blade for protection). Both people coordinate the cut – usually one leads and the other stabilizes. The stance is balanced, and the motion often involves the whole body: the chef will draw the blade toward themselves in a smooth motion, using their body weight to keep it steady.

One long draw cut:

The hallmark technique is to make one continuous “draw cut” through the fish whenever possible. For example, to remove a fillet from a tuna’s side, the tip of the blade is inserted near the tail, then the chef draws the knife lengthwise along the backbone to the head in one stroke, separating the entire side of the fish in one go. This single stroke minimizes saw marks and creates a clean, even cut surface. It takes practice to apply the right pressure and angle for the entire length of the fish.

Using the tip vs. the full blade:

The long blade allows multitasking – chefs often use the lower part of the blade for big cuts and the tip for fine trimming in the same motion. For instance, as the main stroke frees a fillet, the tip of the knife might be used to carefully cut through any remaining connective tissue or to navigate around the collarbone.

The earlier discussion about the pointed tip’s role comes into play here: that tip is used to free meat from tricky spots (like gently tracing around rib bones to peel off the belly meat without leaving scraps). It’s almost like having a fillet knife and a boning knife in one – you just shift which part of the maguro bocho’s blade you’re using.

Two-person teamwork:

In many traditional maguro dismantling scenes, you’ll see two people working together on one tuna with a single long knife. Typically, the lead cutter holds the handle and guides the cut, while an assistant supports the blade’s far end. The assistant’s job is to keep the blade aligned and prevent it from flexing too much or dropping, especially at the very end of a cut.

They often hold the blade with a towel for grip and to avoid cuts. This teamwork allows very controlled, even cutting on huge fish. It’s a bit like two people sawing a log, except in this case it’s about guiding a precise slice rather than brute force sawing. If you ever are in the assistant role, remember to communicate with the lead cutter and move in sync – safety and coordination are paramount.

Safety considerations:

A maguro bocho is extremely sharp and long, so safety is critical. Never point the blade toward anyone (including your assistant or spectators). Make sure the fish is securely positioned so it won’t roll or shift unpredictably during a cut. After each cut, carefully set the knife down in a safe place – due to its length, even laying it across a table can be hazardous if the tip sticks out.

In professional settings, handlers immediately clean the blade of slippery fish oils and blood, reducing slip risk when gripping the handle for the next cut. Many will sheath the blade when not actively cutting. If doing a public tuna-cutting demonstration, it’s wise to rope off the area and ensure no bystanders are within the arc of the blade. Planning your “escape route” for the knife is part of using it – know where the blade will go if a cut completes suddenly, and have a clear spot to set it down.

YUKIKO: “The first time I participated in a tuna fillet demo, I was actually a bit nervous handling the maguro bocho – it’s almost as tall as me! Gensaku-san insisted I practice the motions with an unsharpened blade first. We literally walked through how I would cut, where the tip travels, where to put it down. It was like choreography. Only after that did we go to a real fish. It gave me a deep respect for the knife: you must treat it like a loaded weapon – always aware of the edge and tip. Once we started cutting, though, I was amazed how smoothly it went. Because we prepared and communicated, the huge fish practically fell apart in perfect fillets with just a few elegant strokes. And nobody lost any fingers – success!”

Efficiency and Presentation

For professional chefs, using a maguro bocho can offer both practical and presentation benefits. In terms of efficiency, as noted, a skilled user can break down a large tuna far faster than with standard knives. What might take 30–40 minutes with a combination of butcher knives, hand saws, and fillet knives can be done in a fraction of that time with a proper tuna knife – experts can fillet a tuna in just a few minutes. Less time butchering means more time the fish stays fresh and on ice, and quicker delivery to customers, which can be crucial in a busy sushi restaurant or market.

Additionally, the quality of the cut portions is higher. Sashimi blocks cut with one clean pull of a razor-sharp maguro bocho have pristine surfaces that reflect light, with no ragged fibers – an indicator of top-grade cutting technique. This matters for the visual appeal of the fish when displayed or served. It also can impact taste and texture, as clean cuts preserve the texture of the fish (no mash or torn muscle).

There’s also an element of showmanship. In front of customers or guests, the sight of a chef confidently wielding a maguro bocho to slice up a giant tuna is unforgettable. Many high-end establishments and events leverage this as a form of culinary entertainment (the “maguro kaitai show”). The maguro bocho’s sword-like allure enhances the spectacle. However, professionals are careful not to let the showmanship compromise the product – the knife is still used with precision to ensure the resulting fillets are immaculate. When done right, a tuna-cutting performance with a maguro bocho impresses the crowd and yields perfect cuts of fish for dinner service. It’s a win-win that can elevate a restaurant’s or market’s reputation.

Choosing a Maguro Bocho: Size and Steel Considerations

If you’re a chef looking to acquire a tuna knife, there are a few key factors to consider in choosing the right one for your needs. Not all maguro bocho are identical – they come in different lengths, materials, and build qualities. Here are some guidelines:

Blade Length:

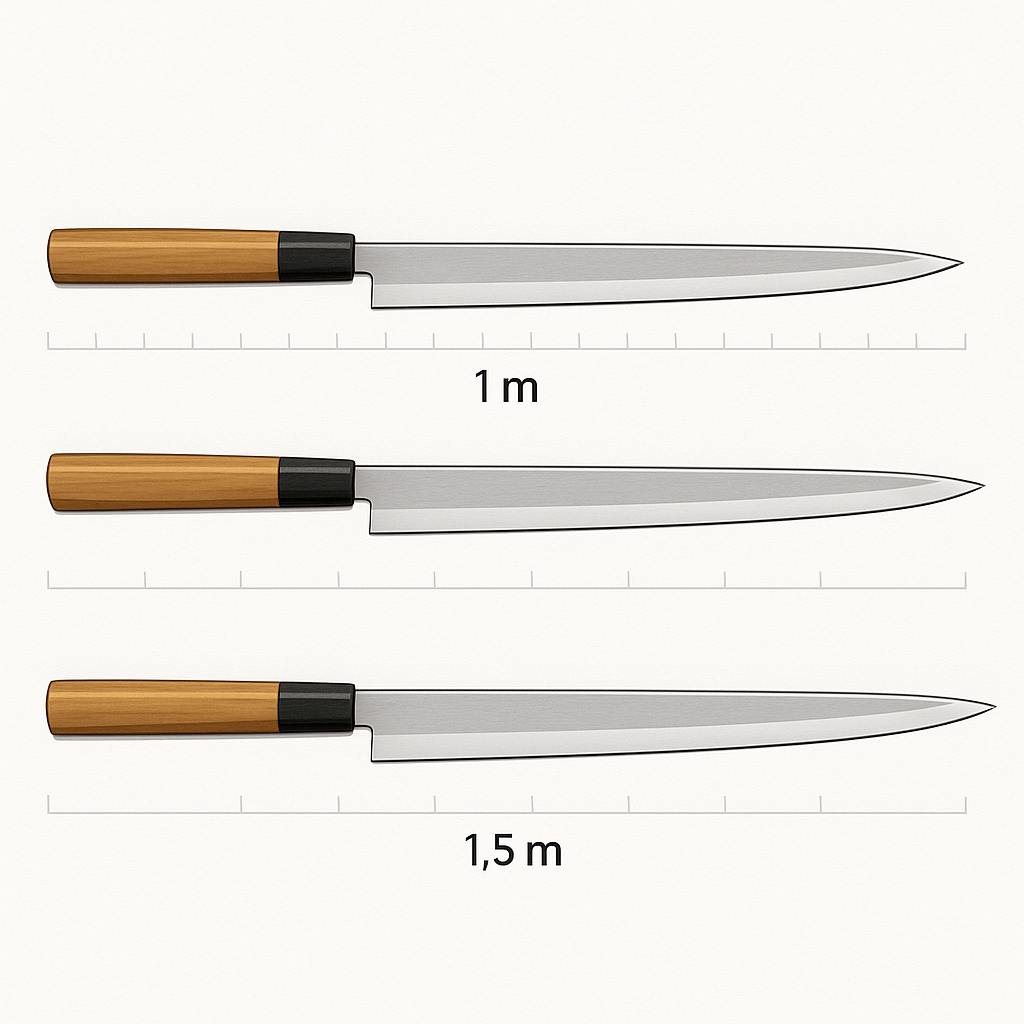

Tuna knives generally come in various lengths such as ~90 cm (3 feet), ~100 cm (3.3 feet), and even 120 cm+ (4–6 feet). Which to choose? It depends on the typical size of fish you handle and your context. For most users, a blade around 90 cm is a practical choice – it’s long enough to handle moderately large tuna and is easier to wield solo. If you frequently process very large tuna (100+ kg) or want the dramatic effect for presentations, a 1 m (100 cm) blade might be ideal, offering that extra reach.

Blades longer than 120 cm are extremely specialized – they can tackle the absolute largest fish or be used in big shows, but require two people and ample space, so only opt for these if you have a specific need. Keep in mind, the longer the blade, the more challenging the handling; there is such a thing as “too much knife” if your environment can’t support it. It’s often said among Japanese fishmongers that you should use the shortest knife that still accomplishes the one-stroke cut – this maximizes control while still providing efficiency. So, match the blade length to the typical tuna size and your working conditions.

Steel (Carbon vs Stainless):

As discussed, carbon steel blades (e.g. traditional white/blue paper steel) can take a super-sharp edge, which is great for clean cuts. If you’re willing to diligently maintain your knife (keep it dry, sharpen and oil regularly) and you want that top performance, a hand-forged carbon steel maguro bocho is a fantastic choice. Brands like Sakai Takayuki or other Sakai smiths produce such knives that experts prize for their cutting ability. On the other hand, stainless steel or semi-stainless blades offer convenience – no worrying about rust spots if you pause during work or if the knife sits unused for a while.

Stainless tuna knives are also often a bit less costly, and modern ones still have high hardness for good edge retention. For chefs doing traveling demonstrations or those in humid climates, stainless might be more practical. Think about your use case: Will you be in a fast-paced market setting where the knife might not get wiped down immediately? Stainless could save you trouble. Are you aiming for the absolute best edge and don’t mind extra care? Then carbon steel is worth it. Some makers now even laminate carbon steel cores with stainless cladding, giving a bit of both worlds (a hard carbon edge with stainless sides for easier maintenance). In summary: choose carbon steel for ultimate sharpness (and commit to its care), choose stainless for low maintenance and durability – both can serve well if properly made.

Build Quality and Flex:

A maguro bocho is a significant investment, and its performance will heavily depend on craftsmanship. Look for a reputable maker or brand known for producing tuna knives. A well-made maguro bocho will have a straight, properly heat-treated blade (no warps), a good balance in hand, and a handle firmly attached. If possible, handle the knife (or a demo) to feel the weight and flex. Some blades are intentionally more flexible; if you’re new, a moderate flex is easier to work with than an ultra-stiff blade. Also consider if you need a sheath – many come with a wooden saya which is highly recommended for safety. Ensure the blade length is measured correctly (some measure just the edge, others include the handle in descriptions). If buying from Japan, note that lengths might be given in sun or shaku (Japanese units: 1 shaku ≈ 30.3 cm).

Legal and Storage:

In the US, there’s generally no restriction on owning a large kitchen knife, but be mindful of transporting it – keep it sheathed and in a secure case when moving it outside your kitchen. You’ll also need a safe place to store it. Due to its size, a maguro bocho might not fit in a regular knife block or drawer! Many chefs hang them on a wall rack or keep them in a custom wooden box. Storing it in its sheath, wrapped in a cloth, in a dry place is advisable (especially for carbon steel to avoid rust).

Maguro Bocho Pricing and Notable Examples

How much does a tuna knife cost? Prices for maguro bocho vary widely based on size, materials, and the maker’s reputation. At the lower end, smaller tuna knives or mass-produced models (perhaps around 30–50 cm blades) can be found in the few-hundred-dollar range. However, the large, high-quality knives used by professionals are not cheap – they are specialty hand-crafted tools. Expect to invest a significant amount for a genuine maguro bocho.

As a ballpark, a good Japanese-made maguro bocho of 90 cm length might cost on the order of $800–$1,500. Longer blades (1 m or more) made by famed craftsmen can run $2,000 or above, due to the extra material and skill required to forge and finish such a large knife. For example, Sakai Takayuki (a well-known Osaka knife brand) offers a top-grade 600 mm tuna knife for around ¥301,200 (approximately $2,500) – painstakingly hand-forged and polished for professional use. Another respected maker, Suisin, produces a 300 mm maguro bocho (designed for smaller tuna or skipjack) priced about ¥150,700 ($1,300). Traditional shops in Japan like Tsukiji’s Aritsugu sell maguro oroshi hocho in the range of ¥70,000–¥120,000 (roughly $600–$1,000), depending on size and whether a sheath is included. These figures give an idea: larger and higher-end = higher price. Custom-made knives or those by renowned masters (sometimes considered functional art pieces) can cost even more, especially if they have decorative elements.

For U.S.-based chefs, some Japanese knife importers and specialty retailers carry maguro bocho. It’s not a common item, so you may need to special order it. Companies like Korin in New York or Japanese knife e-commerce sites might have a few in stock. As of now, for instance, a 21-inch (540 mm) Suisin tuna knife might be listed around $1,800, and a smaller 12-inch one at $1,300. These are serious investments, but they are built to last a lifetime of service. Given that breaking down a single large tuna can yield tens of thousands of dollars in sushi portions, the cost of a proper knife is justified for a professional operation.

When purchasing, ensure you’re getting the real deal – there are novelty “tuna swords” on the market that are more for display (sometimes very cheap, but not practical or food-safe). A true maguro bocho from a knifemaker will use proper cutlery steel and come sharpened ready for work. It will also typically have a well-fitted handle and often a sheath. If you see a price that’s “too good to be true” for a huge knife, double-check the source and quality. Remember, forging a 5-foot steel blade that can actually cut fish is no small feat – the price will reflect that.

YANAGAWA: “I saved up for my own maguro bocho for years. It cost me as much as a small used car, no joke. But let me tell you, the first time I used it on a big tuna, I knew it was worth it. The blade sailed through the fish like butter. Cheaper knives I’d tried would struggle, flex oddly or dull quickly. My hand-forged knife from Sakai holds its edge so well I can process multiple tuna in a day without needing to resharpen. And when I do sharpen it, it hones to a scary sharpness. It was expensive, yes, but it has paid for itself in performance and durability. For any serious sushi chef breaking down whole tuna, investing in a quality maguro bocho is a game-changer.”

In summary, a tuna knife (maguro bocho) is a unique and powerful tool in a chef’s arsenal, purpose-built for slicing up the ocean’s largest fish. For U.S.-based chefs who occasionally (or regularly) handle whole tuna, understanding this knife is crucial – even if you don’t own one, you may find yourself assisting in a tuna breakdown at some point. From its sword-like length that enables single-stroke fillets, to its finely honed tip for precision, to the tradition and craftsmanship behind it, the maguro bocho represents the pinnacle of specialty Japanese cutlery.

It’s a knife that commands respect: respect for its sharpness and size, and respect for the skill required to use it effectively. But under the guidance of experienced hands (and perhaps a mentor like Gensaku-san!), a tuna knife can elevate your butchery of large fish to an art form. Whether you aim to perform dramatic tuna-cutting shows or just want the most efficient way to process a big catch, the maguro bocho stands ready – an awe-inspiring blade that truly lives up to its legendary reputation among Japanese chefs.

Comments